Chapter IX: Ceyx and Halcyone: or The Halcyon Birds

Scenes from Ovid's Metaorphoses Book IX

Dioscorides may have meant the same as Meleager and others when they praised the voice of the halcyon. The halcyon is generally taken to be the kingfisher, and kingfishers have no voice at all: just a squeak or whistle. So far as I know, there is only one species of singing kingfisher, and Meleager is not likely to have known this bird, since it lives in South America.

The blunder is all the more difficult to explain, because Meleager and the rest of them were pretty close observers, full of impartial sympathy for birds and beasts. Perhaps there is no blunder at all. Perhaps we find ourselves here face to face with a change in literary taste. Swans and kingfishers - always supposing halcyon to represent the kingfisher - being birds of beautiful plumage were credited with voices to match.

As regards to the songs of halcyon and swan, we shall perhaps come round to Prof. D'Arcy Thompson's view that both of them veiled, and still hide, some mystical allusion

It is a puzzling chapter in birdlore.

Be xouthos what it may, it is curious to observe that these modern birdlike attributes have been grafted in the Anthology upon that earlier and mythical conception of the halcyon with which we are ill familiar — or rather, not grafted upon it but only scored, so to speak, over its surface : to what end?

In order, maybe, to give to that other one, that old and hazy one, an air of probability, of tangibility, of modernity.

If this be correct, we have in the non-Aristotelean halcyon of the Anthology an interesting phenomenon. It is a kind of palimpsest; or a composite fowl into which the tern-element (Tristram) has been made to enter; a fowl which these poets were determined should be alive, in order that they might project into it certain fond dreams and aspirations of their own.

They seem to have argued that such a creature, if it did not exist in nature, ought to be made to exist. Hence its resuscitation from the shadowy realms of legend; hence those flesh-and-blood characteristics. And we cannot but agree with the poets, supposing this to have been their intention. To invest a dream with life, with actuality, has always been their privilege. Here is an epitaph (7, 292) on a 'drowned man by Theon, father of Hypatia:

Lenaeus! Thee perhaps the halcyons cherished keep,

But mute o'er a dank tomb thy mother tears doth weep.

In another passage (Didot III, 2, 634) a mother deprived by death of her children is pictured as lamenting like a halcyon by the shore..

Macpherson (p. 152) says that the halcyon was well known to the people of Etruria, who figured its graceful form upon their coins. This is a blunder; he means Eretria, which is not the same thing. The coin in question is one portraying a bird on the back of a cow, a bird which Canon Tristram in an article I have not seen (Ibis, 1893; see Warde Fowler, p. 241) identified with a tern: Tristram's contention being that the halcyon of the ancients was not a kingfisher but a tern.

Here is a reproduction, natural size, of the coin in question, which D'Arcy Thompson (p. 31) explains in an astronomical sense. I confess that both its relative size, and its peculiar pose, remind me strongly of the tern. The British Museum authorities tell me it is generally taken to be a swallow or a starling (the latter of which is often seen in company of cows).

What mitigates against Tristram's tern-theory is that the halcyon has been described by ancient writers — by most of them as rare, and of lonely habits. Both these attributes apply to the kingfisher; neither to the tern. It should be remembered that the kingfisher, in these regions, is nearly always seen on or near the sea.

From Birds and Beasts of the Greek Anthology by Norman Douglas

CEYX was king of Thessaly, where he reigned in peace,

without violence or wrong. He was son of Hesperus, the Day–star, and

the glow of his beauty reminded one of his father. Halcyone, the daughter of Æolus, was his wife, and devotedly

attached to him.

Now Ceyx was in deep affliction for the loss of his brother,

Daedalion, and direful

prodigies following his brother’s death made him feel as if

the gods were hostile to him. He thought best, therefore, to make

a voyage to Carlos in Ionia, to consult the oracle of Apollo. But as soon as he disclosed

his intention to his wife Halcyone, a shudder ran through her

frame, and her face grew deadly pale.

[ See: The Transformation of Daedalion ]

“What fault of mine, dearest husband, has turned your affection from me? Where is that love of me that used to be uppermost in your thoughts? Have you learned to feel easy in the absence of Halcyone? Would you rather have me away;”

She also endeavoured to discourage him, by describing the violence of the winds, which she had known familiarly when she lived at home in her father’s house,– Æolus being the god of the winds, and having as much as he could do to restrain them.

[ See: Weather and Folk Lore of Peterborough and District ]

“They rush together,” said she, “with such fury that fire flashes from the conflict. But if you must go,” she added, “dear husband, let me go with you, otherwise I shall suffer not only the real evils which you must encounter, but those also which my fears suggest.”

These words weighed heavily on the mind of King Ceyx, and it was no less his own wish than hers to take her with him, but he could not bear to expose her to the dangers of the sea. He answered. therefore, consoling her as well as he could, and finished with these words:

“I promise, by the rays of my father the Day–star, that if fate permits I will return before the moon shall have twice rounded her orb.”

When he had thus spoken, he ordered the vessel to be drawn out of the shiphouse, and the oars and sails to be put aboard When Halcyone saw these preparations she shuddered, as if with a presentiment of evil. With tears and sobs she said farewell, and then fell senseless to the ground.

Ceyx would still have lingered, but now the young men grasped their oars and pulled vigorously through the waves, with long and measured strokes. Halcyone raised her streaming eyes, and saw her husband standing on the deck, waving his hand to her. She answered his signal till the vessel had receded so far that she could no longer distinguish his form from the rest. When the vessel itself could no more be seen, she strained her eyes to catch the last glimmer of the sail, till that too disappeared. Then, retiring to her chamber, she threw herself on her solitary couch.

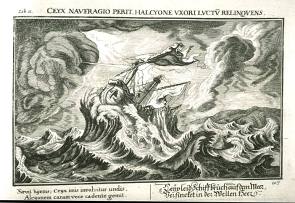

Meanwhile they glide out of the harbour, and the breeze plays among the ropes. The seamen draw in their oars, and hoist their sails. When half or less of their course was passed, as night drew on, the sea began to whiten with swelling waves, and the east wind to blow a gale.

The master gave the word to take in sail, but the storm forbade obedience, for such is the roar of the winds and waves his orders are unheard. The men, of their own accord, busy themselves to secure the oars, to strengthen the ship, to reef the sail. While they thus do what to each one seems best, the storm increases. The shouting of the men, the rattling of the shrouds, and the dashing of the waves, mingle with the roar of the thunder. The swelling sea seems lifted up to the heavens, to scatter its foam among the clouds; then sinking away to the bottom assumes the colour of the shoal–a Stygian blackness.

The vessel shares all these changes. It seems like a wild beast that rushes on the spears of the hunters. Rain falls in torrents, as if the skies were coming down to unite with the sea. When the lightning ceases for a moment, the night seems to add its own darkness to that of the storm; then comes the flash, rending the darkness asunder, and lighting up all with a glare.

Skill fails, courage sinks, and death seems to come on every wave. The men are stupefied with terror. The thought of parents, and kindred, and pledges left at home, comes over their minds. Ceyx thinks of Halcyone. No name but hers is on his lips, and while he yearns for her, he yet rejoices in her absence. Presently the mast is shattered by a stroke of lightning, the rudder broken, and the triumphant surge curling over looks down upon the wreck, then falls, and crushes it to fragments.

Some of the seamen, stunned by the stroke, sink, and rise no more; others cling to fragments of the wreck. Ceyx, with the hand that used to grasp the sceptre, holds fast to a plank, calling for help,– alas, in vain,–upon his father and his father–in–law. But oftenest on his lips was the name of Halcyone. To her his thoughts cling. He prays that the waves may bear his body to her sight, and that it may receive burial at her hands. At length the waters overwhelm him, and he sinks. The Day–star looked dim that night. Since it could not leave the heavens, it shrouded its face with clouds.

In the meanwhile Halcyone, ignorant of all these horrors, counted the days till her husband’s promised return. Now she gets ready the garments which he shall put on, and now what she shall wear when he arrives. To all the gods she offers frequent incense, but more than all to Juno.

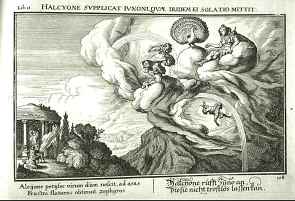

For her husband, who was no more, she prayed incessantly: that be might be safe; that he might come home; that he might not, in his absence, see any one that he would love better than her. But of all these prayers, the last was the only one destined to be granted. The goddess, at length, could not bear any longer to be pleaded with for one already dead, and to have hands raised to her altars that ought rather to be offering funeral rites. So, calling Iris, she said, “Iris, my faithful messenger, go to the drowsy dwelling of Somnus, and tell him to send a vision to Halcyone in the form of Ceyx, to make known to her the event.”

Iris puts on her robe of many colours, and tinging the sky with her bow, seeks the palace of the King of Sleep. Near the Cimmerian country, a mountain cave is the abode of the dull god Somnus. Here Phoebus dares not come, either rising, at midday, or setting. Clouds and shadows are exhaled from the ground, and the light glimmers faintly. The bird of dawning, with crested head, never there calls aloud to Aurora, nor watchful dog, nor more sagacious goose disturbs the silence. No wild beast, nor cattle, nor branch moved with the wind, nor sound of human conversation, breaks the stillness. Silence reigns there; but from the bottom of the rock the River Lethe flows, and by its murmur invites to sleep. Poppies grow abundantly before the door of the cave, and other herbs, from whose juices Night collects slumbers, which she scatters over the darkened earth.

There is no gate to the mansion, to creak on its hinges, nor any watchman; but in the midst a couch of black ebony, adorned with black plumes and black curtains. There the god reclines, his limbs relaxed with sleep. Around him lie dreams, resembling all various forms, as many as the harvest bears stalks, or the forest leaves, or the seashore sand grains.

[ See: 10,000 Dreams Interpreted by Gustavus Hindman Miller ]

[ See: On Dreams by Aristotle ]

[ See: On Sleep and Sleeplessness by Aristotle ]

[ See: The Secret of Dreams By Yacki Raizizun ]

As soon as the goddess entered and brushed away the dreams that hovered around her, her brightness lit up all the cave. The god, scarce opening his eyes, and ever and anon dropping his beard upon his breast, at last shook himself free from himself, leaning on his arm, inquired her errand,– for he knew who she was. She answered,

“Somnus, gentlest of the gods, tranquillizer of minds and soother of care–worn hearts, Juno sends you her commands that you despatch a dream to Halcyone, in the city of Trachine, representing her lost husband and all the events of the wreck.”

Having delivered her message, Iris hasted away, for she could not longer endure the stagnant air, and as she felt drowsiness creeping over her, she made her escape, and returned by her bow the way she came. Then Somnus called one of his numerous sons,– Morpheus,– the most expert in counterfeiting forms, and in imitating the walk, the countenance, and mode of speaking, even the clothes and attitudes most characteristic of each. But he only imitates men, leaving it to another to personate birds, beasts, and serpents. Him they call Icelos; and Phantasos is a third, who turns himself into rocks, waters, woods, and other things without life. These wait upon kings and great personages in their sleeping hours, while others move among the common people. Somnus chose, from all the brothers, Morpheus, to perform the command of Iris; then laid his head on his pillow and yielded himself to grateful repose.

Morpheus flew, making no noise with his wings, and soon came to the Haemonian city, where, laying aside his wings, he assumed the form of Ceyx. Under that form, but pale like a dead man, naked, he stood before the couch of the wretched wife. His beard seemed soaked with water, and water trickled from his drowned locks. Leaning over the bed, tears streaming from his eyes, he said,

“Do you recognize your Ceyx, unhappy wife, or has death too much changed my visage? Behold me, know me, your husband’s shade, instead of himself. Your prayers, Halcyone, availed me nothing. I am dead. No more deceive yourself with vain hopes of my return. The stormy winds sunk my ship in the AEgean Sea, waves filled my mouth while it called aloud on you. No uncertain messenger tells you this, no vague rumour brings it to your ears. I come in person, a shipwrecked man, to tell you my fate. Arise! give me tears, give me lamentations, let me not go down to Tartarus unwept.”

To these words Morpheus added the voice, which seemed to be that of her husband; he seemed to pour forth genuine tears; his hands had the gestures of Ceyx.

Halcyone, weeping, groaned, and stretched out her arms in her sleep, striving to embrace his body, but grasping only the air.

“Stay!” she cried; “whither do you fly? let us go together.”

Her own voice awakened her. Starting up, she gazed eagerly around, to see if he was still present, for the servants, alarmed by her cries, had brought a light. When she found him not, she smote her breast and rent her garments. She cares not to unbind her hair, but tears it wildly. Her nurse asks what is the cause of her grief.

“Halcyone is no more,” she answers, “she perished with her Ceyx. Utter not words of comfort, he is shipwrecked and dead. I have seen him, I have recognized him. I stretched out my hands to seize him and detain him. His shade vanished, but it was the true shade of my husband. Not with the accustomed features, not with the beauty that was his, but pale, naked, and with his hair wet with sea water, he appeared to wretched me. Here, in this very spot, the sad vision stood,”–

and she looked to find the mark of his footsteps.

“This it was, this that my presaging mind foreboded, when I implored him not to leave me, to trust himself to the waves. Oh, how I wish, since thou wouldst go, thou hadst taken me with thee! It would have been far better. Then I should have had no remnant of life to spend without thee, nor a separate death to die. If I could bear to live and struggle to endure, I should be more cruel to myself than the sea has been to me. But I will not struggle, I will not be separated from thee, unhappy husband. This time, at least, I will keep thee company. In death, if one tomb may not include us, one epitaph shall; if I may not lay my ashes with thine, my name, at least, shall not be separated.”

Her grief forbade more words, and these were broken with tears and sobs.

It was now morning. She went to the seashore, and sought the spot where she last saw him, on his departure.

“While he lingered here, and cast off his tacklings, he gave me his last kiss.”

While she reviews every object, and strives to recall every incident, looking out over the sea, she descries an indistinct object floating in the water. At first she was in doubt what it was, but by degrees the waves bore it nearer, and it was plainly the body of a man. Though unknowing of whom, yet, as it was of some shipwrecked one, she was deeply moved, and gave it her tears, saying,

“Alas! unhappy one, and unhappy, if such there be, thy wife!”

Borne by the waves, it came nearer. As she more and more nearly views it, she trembles more and more. Now, now it approaches the shore. Now marks that she recognizes appear. it is her husband! Stretching out her trembling hands towards it, she exclaims,

“O dearest husband, is it thus you return to me?”

There was built out from the shore a mole, constructed to break the assaults of the sea, and stem its violent ingress. She leaped upon this barrier and (it was wonderful she could do so) she flew, and striking the air with wings produced on the instant, skimmed along the surface of the water, an unhappy bird.

As she flew, her throat poured forth sounds full of grief, and like the voice of one lamenting. When she touched the mute and bloodless body, she enfolded its beloved limbs with her new–formed wings, and tried to give kisses with her horny beak. Whether Ceyx felt it, or whether it was only the action of the waves, those who looked on doubted, but the body seemed to raise its head. But indeed he did feel it, and by the pitying gods both of them were changed into birds. They mate and have their young ones. For seven placid days, in winter time, Halcyone broods over her nest, which floats upon the sea. Then the way is safe to seamen. Æolus guards the winds and keeps them from disturbing the deep. The sea is given up, for the time, to his grandchildren.

[ See: The Story of Ceyx and Alcyone ]

[ See: Birds and Beasts of the Greek Anthology ]

The following lines from Byron’s “Bride of Abydos” might seem borrowed from the concluding part of this description, if it were not stated that the author derived the suggestion from observing the motion of a floating corpse:

“As shaken on his restless pillow,

His head heaves with the heaving billow;

That hand, whose motion is not life,

Yet feebly seems to menace strife,

Flung by the tossing tide on high,

Then levelled with the wave...”

[ See: Byron's Bride of Abydos ]

Milton, in his “Hymn on the Nativity,” thus alludes to the fable of the Halcyon:

“But peaceful was the night

Wherein the Prince of light

His reign of peace upon the earth began;

The winds with wonder whist

Smoothly the waters kist

Whispering new joys to the mild ocean,

Who now hath quite forgot to rave

While birds of calm sit brooding on the charmed wave.”

[ See: On The Morning Of Christ's Nativity ]

Keats also, in “Endymion,” says:

“O magic sleep! O comfortable bird

That broodest o’er the troubled sea of the mind

Till it is hushed and smooth.”

[ See: Poems 1817 By John Keats ]