|

|

Latin American Mythology

By Hartley Burr Alexander

CHAPTER II. MEXICO

I Middle America

II Conquistadores

III The Aztec Pantheon

IV The Great Gods:

- Huitzilopochtli

- Tezcajjfcoca

- Quetzalcoatl

- Tlaloc and Chalchiuhtlicue

V The Powers of Life

VI The Powers of Death

I. MIDDLE AMERICA

FROM the Rio Grande to the southern continent extends the great land bridge connecting North and South America, forming a region which might properly be called Middle America. This region divides naturally into several sections. To the north is the body of Mexico, its coastal lands mounting abruptly on the western side, but rising more gradually on the eastern littoral toward the broad central plateau, the shape of which roughly triangular, with its apex in the lofty mountains of the south conforms to that of the whole land north of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. Next to this is the low-lying peninsular region of Yucatan, ascending into mountains toward the Pacific, and forming a great broadening of the southward tapering land. A second bulge is Central America, lying between the Gulf of Honduras and the Mosquito Gulf, and terminating in the thin Isthmus forming an arc about the Bay of Panama.

The physiography of the region is an index to its preColumbian ethnography. 1 The northern portion, including Lower California and, roughly, the mainlands in its latitudes, was a region of wild tribes, the best of them much inferior in culture to the Pueblo Indians on the Gila and the upper Rio Grande, and the lowest as destitute of arts as any in America. Yuman and Waicurian tribes in Lower California; Seri on the Island of Tiburon and the neighbouring mainland; Piman in the north central and western mainlands; Apache in the desert-like lands south of the Rio Grande; and Tamaulipecan on the east, coasting the Gulf of Mexico these are the principal groups of this region, peoples whose ideas and myths differ little from those of their kindred groups of the arid South-west of North America. The Piman group, however, possesses a special interest in that it forms a possible connexion between the Shoshonean to the north and the Nahuatlan nations of the Aztec world. Such peoples as the Papago, Yaqui, Tarahumare, and Tepehuane are the wilder cousins of the Nahua, while the Tepecano, Huichol, and Cora tribes, just to the south, distinctly show Aztec acculturation. In general, the Mexican tribes north of the Tropic of Cancer belong, in habit and thought, with the groups of the South-West of the northern continent; ethnically, Middle America falls south of the Tropic.

Below this line, extending as far as the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, is the region dominated by the empire of the Aztec, marked by the civilization which bears their name. 2 As a matter of fact, although at the time of the culmination of their power this whole region was politically subordinated to the Aztec (it was not completely conquered by them), it contained several centres of culture, each in degree distinct. To the north, about the Panuco, were the Huastec, a branch of the Maya stock; while immediately south of them, and also on the Gulf Coast, were the Totonac, possibly of Maya kinship. The central highlands, immediately west of these peoples, were occupied by the Otomi, primitive and warlike foes of the Aztec emperors. On their west, in turn, the Otomi had a common frontier with Nahuatlan tribes Huichol, Cora, and others forming a transitional group between the wild tribes of the north and the civilized Nahua. Quite surrounded by Nahuatlan and Otomian tribes was the Tarascan stock of Michoacan, a group of peoples whose culture certainly antedates that of the Nahua, of whom, indeed, they may have been the teachers. Still to the south their territories nearly conter- minous with the state of Oaxaca were the Zapotecan peoples, chief among them the Zapotec and Mixtec, whose civilization ranks with those of Nahua and Maya in individual quality, while in native vitality it has proved stronger than either.

The Zoquean tribes (Mixe, Zoque, and others), back from the Gulf of Tehuantepec, form a transition to the next great culture centre, that of the Maya nations. The territories of this most remarkable of all American civilizations included the whole of Yucatan, the greater portions of Tabasco, Chiapas, and Guatemala, and the lands bordering on both sides of the Gulf of Honduras. Thus the Mayan regions dominate the strategy of the Americas, since they not only control the juncture of the continents, but, stretching out toward the Greater Antilles, command the passage between the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea. It is easily conceivable that, had a free maritime commerce grown up, the Maya might have become, not merely the Greeks, but the Romans, of the New World.

Central America, occupied by no less than a dozen distinct linguistic stocks, forms a fourth cultural district. Its peoples show not only the influences of the Maya and Nahua to the north (a tribe of the Nahuatlan stock had penetrated as far south as Lake Nicaragua), but also of the Chibchan civilization of the southern continent, dominant in the Isthmus of Panama, and extending beyond Costa Rica up into Nicaragua. In addition, there is more than a suggestion of influence from the Antilles and from the sea-faring Carib. Here, we can truly say, is the meeting-place of the continents.

The nodes of interest in the culture and history of Middle America are the Aztec and Maya civilizations, which are justly regarded as marking the highest attainment of native Americans. 3 Neither Aztec nor Maya could vie with the Peruvian peoples in the engineering and political skill which made the empire of the Incas such a marvel of organization; but in the general level of the arts, in the intricacy of their science, and above all in the possession of systems of hieroglyphic writing and of monumental records the Middle Americans had touched a level properly comparable with the earliest civilizations of the Old World, nor can theirs have been vastly later than Old World culture in origin.

In a number of particulars the civilizations of the Middle and South American centres show curious parallels. In each case we are in the presence of an aggressively imperial highland (Aztec, Inca) and of a decadent lowland (Maya, Yunca) culture. In each case the lowland culture is the more advanced aesthetically and apparently of longer history. Both highland powers clearly depend upon remote highland predecessors for their own culture (Aztec harks back to Toltec, Inca to Tiahuanaco); and in both regions it is a pretty problem for the archaeologist to determine whether this more remote high-land civilization is ancestrally akin to the lowland. Again, in both the apogee of monument building and of the arts seems to have passed when the Spaniards arrived; indeed, empire itself was weakening. The Aztec and the Inca tribes (perhaps the most striking parallel of all) emerged from obscurity about the same time to proceed on the road to empire, for the traditional Aztec departure from Aztlan and the Inca departure from Tampu Tocco alike occurred in the neighbourhood of 1 200 A. D. Finally, it was Ahuitzotl,' the predecessor of Montezuma II, who brought Aztec power to its zenith, and it was Huayna Capac, the father of Atahualpa, who gave Inca empire its greatest extent; while both the Aztec empire under Montezuma, which fell to Cortez in 1519, and the Inca empire under Atahualpa, conquered by Pizarro in 1524, were internally weakening at the time. But the crowning misfortune common to the two empires was the possession of gold, maddening the eyes of the conquistadores.

II. CONQUISTADORES

4In 1517 Hernandez de Cordova, sailing from Cuba for the Bahamas, was driven out of his course by adverse gales; Yucatan was discovered; and a part of the coast of the Gulf of Campeche was explored. Battles were fought, and hard-ships were endured by the discoverers, but the reports of a higher civilization which they brought back to Cuba, coupled with specimens of curious gold-work, induced the governor of the island to equip a new expedition to continue the exploration. This venture, of four vessels under the command of Juan de Grijalva, set out in May, 1518, and following the course of its predecessor, coasted as far as the province of Panuco, visiting the Isla de los Sacrificios near the site of the future Vera Cruz and doing profitable trading with some of the vassals of the Aztec emperor. A caravel which he dispatched to Cuba with some of his golden profit induced the governor to undertake a larger military expedition to effect the conquest of the empire discovered; for now men began to realize that a truly imperial realm had been revealed. This third expedition was placed under the command of Hernando Cortez; it sailed from Cuba in February, 1519, and landed on the island of Cozumel, in Maya territory, where the Spaniards! '} were profoundly impressed at finding the Cross an object oft veneration. The course was resumed, and a battle was fought near the mouth of the Rio de Tabasco; but Cortez was in search of richer lands and so moved onward, beyond the lands of the Maya, until on Good Friday, April 21, 1519, he landed with all his forces on the site of Vera Cruz. The two years of the Conquest followed the tale of which, for fantastic and romantic adventure, for egregious heroism and veritable gluttony of bloodshed, has few competitors in human annals: its climacterics being the seizure of Montezuma in November, 1519; la noche triste, July i, 1520, when the invaders were driven from Tenochtitlan; and, finally, the defeat and capture of Guatemotzin, August 13, 1521.

The reader of the tale cannot but be profoundly moved both by what the Spaniards found and by what they did. He will be moved with regret at the wanton destruction of so much that was in its way splendid in Aztec civilization. He will be moved with revulsion and wonder that such a civilization could support a religion which, though not without elements of poetic exaltation, was drugged with obscene and bloody rites ; and he will feel only a shuddering thankfulness that this faith is of the past. But when he turns to the agents of its destruction and reads their chronicles, furious with carnage, he will surely say, with Clavigero, that "the Spaniards cannot but appear to have been the severest instruments fate ever made use of to further the ends of Providence," and amid conflicting horrors he will be led again into regretful sympathy for the final victims.

An apologist for human nature would say that neither con- quistador nor papa (as the Spaniards named the Aztec priest) was quite so despicable as his deeds, that both were moved by a faith that had redeeming traits. Outwardly, aesthetically, the whole scene is bizarre and devilish ; inwardly, it is not without devotion and heroism. Bernal Diaz del Castillo, adventurer not only with Cortez, but with Cordova and Grijalva before him, one of the sturdiest of the conquerors and destined to be their foremost chronicler, records for us one unforgettable incident which presents the whole inwardness and outwardness of the situation gorgeous cruelty and simple humanity in a single image. It was four days after the army of Cortez had entered the Mexican capital; and after having been shown the wonders of the populous markets of Tenochtitlan, the visitors were escorted, at their own request, to the platform top of the great teocalli overlooking Tlatelolco, the mart of Mexico. From the platform Montezuma proudly pointed to the quartered city below, and beyond that to the gleaming lake and the glistening villages on its borders all a local index of his imperial domains. "We counted among us," says the chronicler, 5 "soldiers who had traversed different parts of the world: Constantinople, Italy, Rome; they said that they had seen nowhere a place so well aligned, so vast, ordered with such art, and covered with so many people." Cortez turned to Montezuma: "You are a great lord," he said. "You have shown us your great cities; show us now your gods."

PLATE V

Aztec goddess, probably Coatlicue, the mother of Huitzilopochtli, an earth goddess. The statue is one of two Aztec monuments (the other being the "Calendar Stone," Plate XIV) discovered under the pavement of the principal plaza of Mexico City in 1790, and is possibly the very image which Bernal Diaz mistook for "Huichilobos". The goddess wears the serpent apron, and carries a death's head at the girdle; her own head is formed of two serpent heads, facing, rising from her shoulders. The im- portance of Coatlicue in Aztec legend is evidenced by the story of the embassy sent to her by Montezuma I. After an engraving in AnMM, first series, Vol. II.

"He invited us into a tower," continues the chronicler, "into a part in form like a great hall where were two altars covered with rich woodwork. Upon the altars were reared two massive forms, like giants with ponderous bodies. The first, placed at the right, was, they say, Huichilobos [Huitzilopochtli], their god of war. His countenance was very large, the eyes huge and terrifying; all his body, including the head, was covered with gems, with gold, with pearls large and small, adherent by means of a glue made from farinaceous roots. The body was cinctured with great serpents fabricked of gold and precious stones; in one hand he held a bow, and in the other arrows. A second little idol, standing beside the great divinity like a page, carried for him a short spear and a buckler rich in gold and gems. From the neck of Huichilobos hung masks of Indians and hearts in gold or in silver surmounted by blue stones. Near by were to be seen burners with incense of copal; three hearts of Indians sacrificed that very day burned there, continuing with the incense the sacrifice that had just taken place. The walls and floor of this sanctuary were so bathed with congealing blood that they exhaled a horrid odour.

"Turning our gaze to the left, we saw there another great mass, of the height of Huichilobos. Its face resembled the snout of a bear, and its shining eyes were made of mirrors called tezcatl in the language of the country; its body was covered with rich gems, in like manner with Huichilobos, for they are called brothers. They adore Tezcatepuca [Tezcatlipoca] as god of the lower worlds, and attribute to him the care of the souls of Mexicans. His body was bound about with little devils having the tails of snakes. About him also upon the walls there was such a crust of blood and the floor so soaked with it that not the butcheries of Castile exhale such a stench. There was to be seen, moreover, the offering of five hearts of victims sacrificed that day. At the culminating point of the temple was a niche of woodwork, richly carved; within it, a statue representing a being half man, half crocodile, enriched with jewels and partly covered by a mantle. They said that this idol was the god of sowings and of fruits; the half of his body contained all the grains of the country. I do not recall the name of this divinity; what I do know is that here also all was soiled with blood, wall and altar, and that the stench was such that we did not delay to go forth to take the air. There we found a drum of immense size; when struck it gave forth a lugubrious sound, such as an infernal instrument could not want. It could be heard for two leagues about, and it was said to be stretched with the skins of gigantic serpents.

"Upon the terrace were to be seen an endless number of things diabolical in appearance: speaking trumpets, horns, knives, many hearts of Indians burned as incense to idols; and all covered with blood in such quantity that I vowed it to malediction! As moreover, everywhere arose the odours of a charnel, it moved us strongly to depart from these exhalations and above all from so repulsive a sight.

"It was then that our general, by means of our interpreter, said to Montezuma, smiling: 'Sire, I cannot understand how being so great a prince and so wise as you are, that you have not perceived in your reflections that your idols are not gods, but evilly named demons. That Your Majesty may recognize this and all your priests be convinced, grant me the grace of finding it good that I erect a Cross upon the height of this tower, and that in the same part of the sanctuary where are your Huichilobos and Tezcatepuca, we construct a shrine and elevate the image of Our Lady; and you will see the fear which she will inspire in these idols, of which you are the dupes.' Montezuma replied partly in anger, while the priests made menacing gestures: 'Sir Malinche, if I had thought that you could offer blasphemies, such as you have just done, I had not shown you my deities. Our gods we hold to be good; it is they who give us health, rains, good harvests, storms, victories, and all that we desire. We ought to adore them and make them sacrifices. What I beg of you is that you will say not a word more that is not in their honour.' Our general, having heard and seeing his emotion, thought best not to reply; so, affecting a gay air, he said : ' It is already the hour that we and Your Majesty must part.' To which Montezuma answered, true, but as for him, he must pray and make sacrifice in expiation of the sin he had committed in giving us access to his temple, which had had for consequence our presentation to his gods and the want of respect through which we had rendered ourselves culpable, blaspheming against them." So the Spaniards departed, leaving Montezuma to his expiatory prayers and no doubt bloody sacrifices.

III. THE AZTEC PANTHEON

6 Within the precincts of the temple-pyramid, and not far from it, was a lesser building which Bernal Diaz describes, a house of idols, diabolisms, serpents, tools for carving the bodies of sacrificed victims, and pots and kettles to cook them for the cannibal repasts of the priests, the entrance being formed by gaping jaws " such as one pictures at the mouth of Inferno, showing great teeth for the devouring of poor souls." The place was foul with blood and black with smoke, "and for my part," says Diaz, "I was accustomed to call it 'Hell.":

It is indeed doubtful whether the human imagination has ever elsewhere conjured up such soul-satisfying devils as are the gods of the Aztec pantheon. Beside them Old World demons seem prankishly amiable sprites: the Mediaeval imagination at best (or worst) gives us but a somewhat deranged barnyard, while even Chinese devils modulate into pleasantly decorative motifs. But the Aztec gods, in their formal presentments, and seldom less in their material characters, ugly, ghastly, foul, afford unalloyed shudders which time cannot still, nor custom stale. To be sure, the ensemble frequently shows a vigour of design which suggests decoration (though the decorative spirit is never sensitive, as it often is in Maya art); but this suggestion is too illusory to abide: it passes like a mist, and the imagination is gripped by the raw horror of the Thing. Aztec religious art seems, in fact, to move in a more primitively realistic atmosphere than that in which the religious art of other peoples has come to similarly adept expression; it shows little of that tendency - which Yucatan and Peru in America, as well as the ancient and Oriental nations, had all attained to subordinate the idea to the expressional form, and to soften even the horrible with the suavity of aesthetic charm. The Aztec gods were as grimly business-like in form as the realities of their service were fearful.

In number these divinities were myriad and in relations chaotic. There were clan and tribal, city and national gods, not only of the victorious race, but of their confederates and subjects, for the Aztec followed the custom of pagan conquerors, holding it safest to honour the deities native to the land; and several of their greatest divinities were assuredly inherited from vanquished peoples Quetzalcoatl and Tlaloc among them though an odd and somewhat amusing fact is that a multitude of the godling idols of ravaged cities were kept in a kind of prison-house in the Aztec capital, where, it was assumed, they were incapable of assisting their former worshippers. There were gods of commerce and industries, headed by Tacatecutli, god of merchant-adventurers, whose "peaceful penetration" opened paths for the imperial armies; gods of potters and weavers and mat-makers, of workers in wood and stone and metal; gods of agriculture, of sowing and ripening and reaping; gods of fishermen; gods of the elements earth, air, fire, and water; gods of mountains and volcanoes; creator-gods; animal-gods; gods of medicine, of disease and death, and of the underworld; deity patrons of drunkenness and of carnal vice, and deity protectors of the flowers which these strange peoples loved. The whole heterogeneous world was filled with divinities, reflecting the old fears of primitive man and the old tumults of history, each god jealous of his right and gluttonous of blood a kind of horrid exteriorization of human passion and desire.

However, this motley pantheon is not without certain principles of order. The regulations of an elaborate social system, divided by clan and caste and rank and guild, are reduplicated in it; for to every phase of Mexican life religious rites and divine tutelage were attached. Still more significant as a means of hierarchic classification is the relation of the divine beings to the divisions of time and space. A cult of the quarters of space and their tutelaries and of the powers of sky-realms above and of earth-realms below is almost universal among American Indian groups showing any advancement in culture; the gods of the quarters, for example, are bringers of wind and rain, upholders of heaven, animal chiefs; the gods above are storm-deities and rulers of the orbs and dominions of light, on the whole beneficent; the powers below, under the hegemony of the earth goddess, are spirits of vegetation and lords of death and things noxious. This is the most primitive stage in which the family of Heaven and Earth begin to assume form as an hierarchic pantheon. But the seasons, beginning with the diurnal alternation of the rule of light and darkness, and proceeding thence to the changing phases of the moon and the seasonal journeys of the sun, constantly shift the domination of the world from deity to deity and from group to group. Thus the lords of day are not the lords of night, nor are the' fates of the mounting morn those of descending eve: the Sun himself changes his disposition with the hours. Similarly, the Moon's phases are tempers rather than forms; and the year, divided among the gods, runs the cycle of their influences.

The Aztec and other pantheons of the civilized Mexicans evince all of these elements with complications. Both cosmography and calendar are more complex than among the more northerly Americans, and there is a veritable tangle of space-craft and time-craft, with astrological and necromantic conceptions, bound up with every human desire and every natural activity. Certainly the most curious feature of this lore is the influence of certain numbers especially four (and five) and nine; and, again, six (and seven) and thirteen. These number-groups are primarily related to space-divisions. Thus four is the number of cardinal points, North, South, East, and West, to which a fifth point is added if the pou sto, or point of the observer, is included; by a process of reduplication, of which there are several instances in North America, the number of earth's cardinal points became the number of the sky-tiers above and of the earth-tiers below, so that the cosmos becomes a nine-storeyed structure, with earth its middle plane. Sometimes (this is characteristic of the Pueblo Indians) orientation is with reference to six points the four directions and the Above and the Below (the pou sto, when added, becomes a seventh a grouping which recalls to us the seven forms of Platonic locomotion up, down, forward, backward, right, left, and axial). With these directions colours, jewels, herbs, and animals are symbolically associated, becoming emblems of the ruling powers of the quarters. The number-groups thus cosmographically formed react upon time-conceptions, especially where ritual is concerned. Thus the Pueblo Indians celebrate lesser festivals of five days (a day of preparation and four of ritual), and greater feasts of nine days (reduplicating the four) the whole, in some cases at least, being comprised in a longer period of twenty days. The rites of the year among the Zuni and some others are divided into two six-month groups, and each month is dedicated to or associated with one of the six colour-symbols of the six directions; while the Hopi a fact of especial interest make use of thirteen points on the horizon for the determination of ceremonial dates.7

The cosmic and calendric orientation of the Mexicans is a complex, with elaborations, of both these number-groups (i. e. four, five, nine, and six, seven, thirteen). According to one conception there are nine heavens above and nine hells beneath. Ometecutli ("Twofold Lord") and Omeciuatl ("Twofold Lady") the male and female powers of generation, dwell in Omeyocan ("the Place of the Twofold") at the culmination of the universe; and it is from Omeyocan that the souls of babes, bringing the lots "assigned to them from the commencement of the world," 8 descend to mortal birth; while in the opposite direction the souls of the dead, after four years of wandering, having passed the nine-fold stream of the underworld, go to find their rest in Chicunauhmictlan, the ninth pit. Nine "Lords of the Night" preside over its nine hours, and potently over the affairs of men. Mictlantecutli, the skeleton god of death, is lord of the midnight hour; the owl is his bird; his consort is Mictlanciuatl ; and the place of their abode, windowless and lightless, is "huge enough to receive the whole world." Over the first hour of night and the first of morning (there are Lords of the Day, too) presides Xiuhtecutli, the fire-god, for the hearth of the universe, like the hearth of the house, is the world's centre.

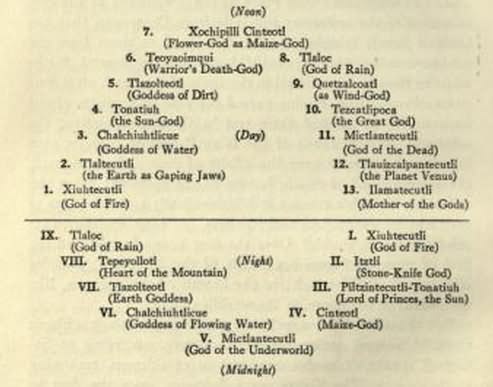

But the ninefold conception of the universe is not without rival. A second notion (of Toltec source, according to Sahagun) speaks of twelve heavens; or of thirteen, reckoning earth as one. The Toltec, says Sahagun, were the first to count the days of the year, the nights, and the hours, and to calculate the movements of the heavens by the movements of the stars; they affirmed that Ometecutli and Omeciuatl rule over the twelve heavens and the earth, and are procreators of all life below. There is some ground for believing that with this there was associated a belief in twelve corresponding under-worlds, for Seler 9 plausibly argues that the five-and-twenty divine pairs of Codex Vaticanus B represent twelve pairs of rulers of hours of the day, twelve of hours of the night, and one intermediate. However, the arrangement which Seler finds predominating is that of thirteen Lords of the Day and nine Lords of the Night implying a commingling of the two systems and this scheme (the day-hour lords following the Aubin Tonalamatl and the Codex Borbonicus, as Seler interprets them) he reconstructs dial-fashion, as follows:

But the gods are patrons not only of the celestial worlds and of the underworlds, hours of the day and of the night; they are also rulers and tutelaries of the quarters of earth and heaven, and of the numerous divisions and periods of time involved in the complicated Mexican calendar. The influences of the cosmos were conceived to vary not merely with the seasonal or solar year of 365 days, but also with the Tonalamatl (a calendric period of 13 x 20, or 260, days); again with a 584-day period of the phases of Venus; and finally with the cycles formed by measuring these periods into one another. Here, it is evident, we are in the presence not only of a scheme capable of utilizing an extensive pantheon, but of one having divinatory possibilities second to no astrology.

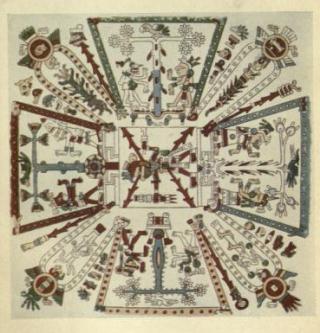

As such it was used by the Mexican priests, and various codices, or pinturas, preserved from the general destruction of Aztec manuscripts are nothing but calendric charts to calculate days for feasts and days auspicious or inauspicious for enterprise. In one of these, the Codex Ferjervary-Mayer, the first sheet is devoted to a figure in the general form of a cross pattee combined with an X, or St. Andrew's cross. This figure, as explained by Seler, 11 affords a graphic illustration of Aztec ideas. It represents the five regions of the world and their deities, the good and bad days of the Tonalamatl the nine Lords of the Night, and the four trees (in form like taucrosses) which rise into the quarters of heaven, perhaps as its support. In the Middle Place, the pou sto, is the red image of Xiuhtecutli, the Fire-Deity "the Mother, the Father of the Gods, who dwells in the navel of the Earth") armed with spears and spear-thrower, while from the divinity's body four streams of blood flow to the four cardinal points, terminating in symbols appropriate to these points East, a yellow hand typifying the sun's ray; North, the stump of a leg, symbol of Tezcatlipoca as Mictlantecutli, lord of the underworld; West, where the sun dies, the vertebrae and ribs of a skeleton; South, Tezcatlipoca as lord of the air, with featherdown in his head-gear. The arms of the St. Andrew's cross terminate in birds quetzal, macaw, eagle, parrot bearing shields upon which are depicted the four day-signs after which the years are named (because, in sequence, they fall on the first day of the year), each year being brought into relation with a correspondingly symbolized world-quarter; within each arm of the cross, below the day-sign, is a sign denoting plenty or famine. But the main part of the design, about the centre, is occupied with symbols of the quarters of the heavens. In each section is a T-shaped tree, surmounted by a bird, with tutelary deities on either side of the trunk. Above, framed in red, the tree rises from an image of the sun, set on a temple, while a quetzal bird surmounts it; the gods on either side are (left) Itztli, the Stone-Knife God, and (right) Tonatiuh, the Sun; the whole symbolizes the tree which rises into the eastern heavens. The trapezoid opposite this, coloured blue, symbol of the west, contains a thorn-tree rising from the body of the dragon of the eclipse (for the heavens descend to darkness in this region) and surmounted by a humming-bird, which, according to Aztec belief, dies with the dry and revives with the rainy season; the attendant deities are Chalchiuhtlicue, goddess of flowing water, and the earth goddess Tlazolteotl, deity of dirt and of sin. To the right, framed in yellow, a thorny tree rises from a dish containing emblems of expiation, while an eagle surmounts it; the attendants are Tlaloc, the rain-god, and Tepeyollotl, the Heart of the Mountains, Voice of the Jaguar all a token of the northern heavens. Opposite this is a green trapezoid containing a parrot-surmounted tree rising from the jaws of the Earth, and having, on one side, Cinteotl, the maize-god, and on the other, Mictlantecutli, the divinity of death. The nine deities, he of the centre and the four pairs, form the group of los Senores de la Noche ("the Lords of Night"); while the whole figure symbolizes the orientation of the world-powers in space and time years and Tonalamatls, earth-realms and sky-realms.

PLATE VI

First page of the Codex Ferjervary-Mayer, representing the five regions of the world and their tutelary deities. Seler's interpretation of this figure is given, in brief, on pages 55-56 of this book.

The recurrence of cross-forms in this and similar pictures is striking: the Greek cross, the tau-cross, St. Andrew's cross. The Codex Vaticanus B contains a series of symbols of the trees of the quarters approximating the Roman cross in form, suggesting the cross-figured tablets of Palenque. In the analogous series of the Codex Borgia, each tree issues from the recumbent body of an earth divinity or underworld deity, each surmounted by a heaven-bird; and again all are cruciform. There is also a tree of the Middle Place in the series, rising from the body of the Earth Goddess, who is masked with a death's head and lies upon the spines of a crocodile "the fish from which Earth was made" surmounted by the quetzal bird (Pharomacrus mocinno), whose green and flowing tail-plumage is the symbol of fructifying moisture and responding fertility " already has it changed to quetzal feathers, already all has become green, already the rainy time is here!" About the stem of the tree are the circles of the world-encompassing sea, and on either side of it, springing also from the body of the goddess, are two great ears of maize. The attendant or tutelar deities in this image are Quetzalcoatl ("the green Feather-Snake"), god of the winds, and Macuilxochitl ("the Five Flowers"), the divinity of music and dancing. Another series of figures in this same Codex represent the gods of the quarters as caryatid-like upbearers of the skies Quetzalcoatl of the east; Huitzilopochtli, the Aztec war-god, of the south; Tlauizcalpantecutli, Venus as Evening Star, of the west; Mictlantecutli, the death-god, of the north. All these, however, are only a few of the many examples of the multifarious cosmic and calendric arrangements of the gods of the Aztec pantheon.

IV. THE GREAT GODS"

On the cosmic and astral side the regnant powers of the Aztec pantheon are the Gaping Jaws of Earth; the Sea as a circumambient Great Serpent; and the Death's-Head God of the Underworld; while above are the Sun wearing a collar of life-giving rays; the Moon represented as marked by a rabbit (for in Mexican myth the Moon shone as brightly as the Sun till the latter darkened his rival by casting a rabbit upon his face); and finally the Great Star, "Lord in the House of Dawn," the planet Venus, characteristically shown with a body streaked red and white, now Morning Star, now Evening Star. The Sun and Venus are far more important than the Moon, for the reason that their periods (365 and 584 days respectively), along with the Tonalamatl (260 days), form the foundation for calendric computations. The regents of the quarters of space and of the divisions of time are ranged in numerous and complex groups under these deities of the cosmos.

But the divinities who are thus important cosmically are not in like measure important politically, nor indeed mythologically, since the great gods of the Aztec, like those of other consciously political peoples, were those that presided over the activities of statecraft war and agriculture and political destiny. In the Aztec capital the central teocalli was the shrine of Huitzilopochtli, the war-god and national deity of the ruling tribe. The teocalli above the market-place, which Bernal Diaz describes, was devoted to Coatlicue, the mother of the war-god, to Tezcatlipoca, the omnipotent divinity of all the Nahua tribes, and, in a second shrine, to Tlaloc, the rain-god, whose cult, according to tradition, was older than the coming of the first Nahua. In a third temple, built in circular rather than pyramidal form, was the shrine of what was perhaps the most ancient deity of all, Quetzalcoatl ("the Feather-Snake"), lord of wind and weather. These Huitzilopochtli, Tezcatlipoca, Quetzalcoatl, and Tlaloc are the gods that are supreme in picturesque emphasis in the Aztec pantheon.

i. HUITZILOPOCHTLI

12The great teocalli of Huitzilopochtli stood in the centre of Tenochtitlan and was dedicated in the year 1486 by Ahuitzotl, the emperor preceding the last Montezuma, with the sacrifice of huge numbers of captive warriors sixty to eighty thousand, if we are to believe the chroniclers. On the platform top of the pyramidal structure, bearing the fane of the war-god and also (as in the case of the temple in the market place) a shrine of Tlaloc, was space, tradition says, for a thousand warriors, and it was here, in 1520, that Cortez and his companions waged their most picturesque battle, fighting their way up the temple stairs, clearing the summit of some four hundred Aztec warriors, burning the fanes, and hurling the images of the gods to the pavements below. After the Conquest the temple was razed, and the Cathedral which still adorns the City of Mexico was erected on or near a site which had probably seen more human blood shed for superstition than has any other in the world.

The name of the war-god, Huitzilopochtli (or Uitzilopochtli), is curiously innocent in suggestion "Humming-Bird of the South" (literally, "Humming-Bird-Left-Side," for in naming the directions the Nahua called the south the "left" of the sun). Humming-bird feathers on his left leg formed part of the insignia of the divinity; the fire-snake, Xiuhcoatl, was another attribute, and the spear-thrower which he carried was serpentine in form; among his weapons were arrows tipped with balls of featherdown; and it was to his glory that gladiatorial sacrifices were held in which captive warriors, chained to the sacrificial rock, were armed with down-tipped weapons and forced to fight to the death with Aztec champions. One of the most romantic of native tales recounts the capture, by wile, of the Tlascalan chieftain, Tlahuicol. Such was his renown that Montezuma offered him citizenship, rather than the usual death by sacrifice, and even sent him at the head of a military expedition in which the Tlascalan won notable victories. But the chieftain refused all proffers of grace, claiming the right to die a warrior's death on the sacrificial stone, and at last, after three years of captivity, Montezuma conceded to him the privilege sought the gladiatorial sacrifice. The Tlascalan is said to have slain eight Aztec warriors and to have wounded twenty before he finally succumbed. It may be remarked in passing that the Tlascalan deity, Camaxtli, the Tarascan Curicaveri, the Chichimec Mixcoatl, and the tribal god of the Tepanec and Otomi, Otontecutli or Xocotl, were similar to, if not identical with, Huitzilopochtli.

The myth of the birth of Huitzilopochtli, which Sahagun relates, throws light upon the character of the divinity. His mother, Coatlicue ("She of the Serpent-Woven Skirt"), dwelling on Coatepec ("Serpent Mountain"), had a family consisting of a daughter, Coyolxauhqui ("She whose Face is Painted with Bells"), and of many sons, known collectively as the Centzonuitznaua ("the Four Hundred Southerners"). One day, while doing penance upon the mountain, a ball of feathers fell upon her, and having placed this in her bosom, it was observed, shortly afterward, that she was pregnant. Her sons, the Centzonuitznaua, urged by Coyolxauhqui, planned to slay their mother to wipe out the disgrace which they conceived to have befallen them; but though Coatlicue was frightened, the unborn child commanded her to have no fear. One of the Four Hundred, turning traitor, communicated to the still unborn Huitzilopochtli the approach of the hostile brothers, and at the moment of their arrival the god was born in full panoply, carrying a blue shield and dart, his limbs painted blue, his head adorned with plumes, and his left leg decked with humming-bird feathers. Commanding his servant to light a torch, in shape a serpent, with this Xiuhcoatl he slew Coyolxauhqui, and destroying her body, he placed her head upon the summit of Coatepec. Then taking up his arms, he pursued and slew the Centzonuitznaua, a very few of whom succeeded in escaping to Uitztlampa ("the Place of Thorns"), the South.

The myth seemingly identifies Huitzilopochtli as a god of the southern sun. The hostile sister is the moon; the brothers are the stars driven from the heavens by the rising sun, whose blue shield is surely 'the blue buckler of the daylit sky; and probably the balls of featherdown tipping his arrows are cloud-symbols. Sahagun describes a sacramental rite in which an image of the god's body, made of grain, was eaten by a group of youths who were for a year the servitors of the deity, with duties so onerous that the young men sometimes fled the country, preferring death at the hands of their enemies a statement which leads to the suspicion that here was some ordeal connected with chivalric advancement. Certainly Huitzilopochtli was a god of warriors, and it is probable that those devoted to him sought the warrior's death, which meant ascent into the skies rather than that descent into murky Mictlan which was the lot of the ordinary. In this connexion the name of the divinity and the humming-bird feather insignia acquire significance; for again it is Sahagun who relates that the souls of ascending warriors, after four years, are "metamorphosed into various kinds of birds of rich plumage and brilliant colour which go about drawing the sweet from the flowers of the sky, as do the humming-birds upon earth."

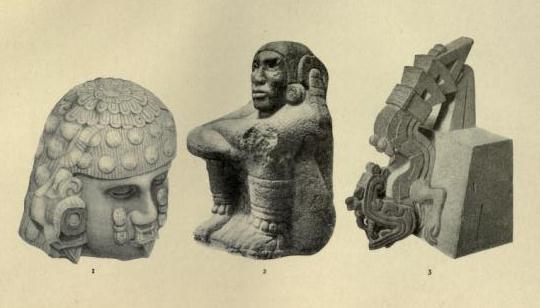

PLATE VII: 1. Colossal stone head representing

Coyolxauhqui, the Moon goddess, sister of Huitzilopochtli. The

head is not a fragment, but bears figures upon its base, and

doubtless represents Coyolxauhqui as slain by the Fire Snake,

Xiuhcoatl, hurled by Huitzilopochtli, and afterwards beheaded by

him. The original is in the Museo Nacional, Mexico.

2. Statue of the god of feasting, Xochipilli, "Lord of Flowers"

(see page 77). The crest is missing. The original is in the

British Museum.

3. The Fire Snake, Xiuhcoatl, as represented in stone. The Fire

Snake is associated with Huitzilopochtli, Tezcatlipoca, and the

fire god, Xiuhtecutli; and stands, perhaps, in a kind of

opposition to the "Green Feather Snake," Quetzalcoatl, the latter

signifying rain and vegetation, the former drought and want (cf.

the hymn to Xipe Totec, page 77). The original is in the British

Museum.

2. TEZCATLIPOCA

13 Tezcatlipoca, or "Smoking Mirror," was so called because of his most conspicuous emblem, a mirror from which a spiral of smoke is sometimes represented as ascending, and in which the god was supposed to see all that takes place on earth, in heaven, and in hell. Frequently the mirror is shown as replacing one of his feet (loss or abnormality of cne foot is common in the Mexican pantheon), explained mythically as severed when the doors of the underworld closed prematurely upon it for Tezcatlipoca in one of his many functions is deity of the setting sun. In other aspects he is a' moon-god, the moon of the evening skies; again, a divinity of the night; or sometimes, with blindfold eyes, a god of the underworld and of the dead; and in the calendric charts he is represented as regent of the northern heavens, although sometimes (perhaps identified with Huitzilopochtli) he is ruler of the south. Probably he is at bottom the incarnation of the changing heavens, symbolized by his mirror, now fiery, now murky, reflecting the encompassed universe. He is the red Tezcatlipoca and the black the heaven of day and the heaven of night. He is the Warrior of the North and the Warrior of the South, symbolizing the course of the yearly sun, which, in the latitude of Mexico, culminates with the alternating seasons to the north and to the south of the zenith. His emblems include the Fire-Snake, symbol of heavenly fires; and again he is Iztli-Tezcatlipoca, the Stone-Knife God of the underworld, of blood-letting penance, and of human sacrifice. Sahagun says of him that he raised wars, enmities, and discords wherever he went; nevertheless, he was the ruler of the world, and from him proceeded all prosperities and enrichments. Frequently he is represented as a jaguar, which to the Mexicans was the dragon of the eclipse, a were-beast, and the patron of magicians; cross-roads were marked by seats for Tezcatlipoca, the god who traversed all ways; and he was called the Wizard and the Transformer. In himself he was invisible and impalpable, penetrating all things; or, if he appeared to men, it was as a flitting shadow; yet he could assume multifarious monstrous forms to tempt and try men, striking them with disease and death. As Yoalli Ehecatl, the Night Wind, he wandered about in search of evil-doers, and sinners summoned him in their confessions. On the other hand, he was "the Youth" (Telpochtli), and as Omacatl ("Two-Reed") he was lord of banquets and festivities.

It is evident that Tezcatlipoca is the Great Transformer, identified with the heavens and all its breaths, twofold in all things: day, night; life, death; good, evil. Certainly he seems to have been held in more awe than any other Mexican god and well merits the supremacy (not political, but religious) which tradition assigns to him. The most notable of the prayers which Sahagun transcribes are filled with poetic veneration for this deity, and had we only these invocations as record not also tales of the fearful human sacrifices we should assuredly assign to their Aztec composers a pure and noble religious sentiment. Perhaps theirs was so, for men's actions everywhere seem worse than the creeds which impel them. Thus, in time of plague the priests prayed:

"O mighty Lord, under whose wings we seek protection, defence, and shelter! Thou art invisible, impalpable, as the air and as the night. I come in humility and in littleness, daring to appear before Thy Majesty. I come uttering my words like one choking and stammering; my speech is wandering, like as the way of one who strayeth from the path and stumbleth. I am possessed of the fear of exciting thy wrath against me rather than the hope of meriting thy grace. But, Lord, do with my body as it pleaseth thee, for thou hast indeed abandoned us according to thy counsels taken in heaven and in hell. Oh, sorrow! thine anger and thine indignation are descended upon us in all our days . . .

"O Lord, very kindly! Thou knowest that we mortals are like unto children which, when punished, weep and sigh, repenting their faults. It is thus that these men, ruined by thy chastisements, reproach themselves grievously. They confess in thy presence; they atone for their evil deeds, imposing penance upon themselves. Lord, very good, very compassionate, very noble, very precious! let the chastisement which thou hast inflicted suffice, and let the ills which thou hast sent in castigation find their end!"

Throughout the prayers there are characterizations of the god, not a few of them echoing a kind of world-weary melancholy that seems so typical of Aztec supplications. When the new king is crowned, the priest prays: "Perchance, deeming himself worthy of his high employ, he will think to perpetuate himself long therein. Will not this be for him a dream of sorrow? Will he find in this dignity received at thy hands an occasion of pride and presumption, till it hap that he despise the world, assuming to himself a sumptuous show? Thy Majesty knoweth well whereto he must come within a few brief days for we men are but thy spectacle, thy theatre, serving for thy laughter and diversion." And when the king is dead: "Thou hast given him to taste in this world a few of thy sweets and suavities, making them to pass before his eyes like the will-o'-the-wisp, which vanisheth in an instant; such is the dignity of the post wherein thou didst place him, and in which he had a few days in thy service, prostrate, in tears, breathing his devoted prayers unto thy Majesty." Again: "Thou art invisible and impalpable, and we believe that thy gaze doth penetrate the stones and into the hearts of the trees, seeing clearly all that is concealed therein. So dost thou see and comprehend what is in our hearts and in our thoughts; before thee our souls are as a waft of smoke or as a vapour that riseth from the earth."

Perhaps the most striking rite in the Aztec year was the springtime sacrifice to Tezcatlipoca near Easter, Sahagun says. In the previous year a youth had been selected from a group of captives trained for the purpose, physically without blemish and having all accomplishments possible. He was trained to sing and to play the flute, to carry flowers and to smoke with elegance; he was dressed in rich apparel and was constantly accompanied by eight pages. The king himself provided for his habiliment, since "he held him already to be a god." For nearly a year this youth was entertained and feasted, honoured by the nobility and venerated by the populace as the living embodiment of Tezcatlipoca. Twenty days before the festival his livery was changed, and his long hair was dressed like that of an Aztec chieftain. Four maidens, delicately reared, were assigned to him as wives, called by the names of four goddesses Xochiquetzal (" Flowering QuetzalPlume"), Xilonen ("Young Maize"), Atlatonan (a goddess of the coast), and Uixtociuatl (goddess of the salt water). Five days previous to the sacrifice a series of feasts and dances was begun, continued during each of the following four days in separate quarters of the city. Then came the final day; the youth was taken beyond the city; his goddess-wives abandoned him; and he was brought to a little road-side temple for the consummation of the rite. He ascended its four stages, breaking a flute at each stage, till at the top he was seized, and the priest opening his breast with a single blow, presented his heart to the sun. Immediately another youth was chosen for the following year, for the Tezcatlipoca must never die. It was said, remarks Sahagun, that this youth's fate signified that those who possess wealth and march amid pleasures during life will end their career in grief and poverty; while Torquemada more grimly comments that "the soul of the victim went down to the company of his false gods, in hell." For the student of to-day, however, the rite is but another significant symbol of the god who dies and is born again.

PLATE VIII: Figure from the Codex Borgia representing the red and the black Tezcatlipoca facing one another across a tlachtli court upon which is shown a sacrificial victim painted with the red and white stripes of the Morning and Evening Star (Venus). The red Tezcatlipoca symbolizes day, the black Tezcatlipoca, night; the ball court is a symbol of the universe; the Morning and Evening Star might very naturally be looked upon as a sacrifice to the heaven god.

In myth Tezcatlipoca plays the leading role as adversary of Quetzalcoatl, the ruler and god of the Toltec city of Tollan. In Sahagun's version of the story, three magicians, Huitzilopochtli, Titlacauan ("We are his Slaves," an epithet of Tezcatlipoca), and Tlacauepan, the younger brother of the others, undertook by magic and wile to drive Quetzalcoatl from the country and to overthrow the Toltec power. The three deities are obviously tribal gods of Nahuatlan nations, and Tezcatlipoca, who plays the chief part in the legends, is clearly the god of first importance at this early period, possibly the principal deity of all the Nahua; he was also the foremost divinity of Tezcuco, which, almost to the eve of the Conquest, was the leading partner in the Aztec confederacy. As the tale goes, Quetzalcoatl was ailing; Tezcatlipoca appeared in the guise of an old man, a physician, and administered to the ailing god, not medicine, but a liquor which intoxicated him. Texcatlipoca then assumed the form of a nude Indian of a strange tribe, a seller of green peppers, and walked before the palace of Uemac, temporal chief of the Toltec. Here he was seen by the chief's daughter, who fell ill of love for him. Uemac ordered the stranger brought before him and demanded of Toueyo (as the stranger called himself) why he was not clothed as other men. "It is not the custom of my country," Toueyo answered. "You have inspired my daughter with caprice; you must cure her," said Uemac. "That is impossible; kill me; I would die, for I do not deserve such words, seeking as I am only to earn an honest living." "Nevertheless, you shall cure her," replied the chief, "it is necessary; have no fear." So he caused the marriage of his daughter with the stranger, who thus became a chieftain among the Toltec. Winning a victory for his new countrymen, he announced a feast in Tollan; and when the multitudes were assembled, he caused them to dance to his singing until they were as men intoxicated or demented; they danced into a ravine and were changed into rocks, they fell from a bridge and became stones in the waters below. Again, in company with Tlacauepan, he appeared in the market-place of Tollan and caused the infant Huitzilopochtli to dance upon his hand. The people, crowding near, crushed several of their number dead; enraged, they slew the performers and, on the advice of Tlacauepan, fastened ropes to their bodies to drag them out; but all who touched the cords fell dead. By this and other magical devices great numbers of the Toltec were slain, and their dominion was brought to an end.

3. QUETZALCOATL

14 The most famous and picturesque of New World mythic figures is that of Quetzalcoatl, although primarily his renown is due less to the undoubted importance of his cult than to his association with the coming and the beliefs of the white men. According to native tradition, Quetzalcoatl had been the wise and good ruler of Tollan in the Golden Age of Anahuac, lawgiver, teacher of the arts, and founder of a purified religion. Driven from his kingdom by the machinations of evil magicians, he departed over the eastern sea for Tlapallan, the land of plenty, promising to return and reinstitute his kindly creed on some future anniversary of the day of his departure. He was described as an old man, bearded, and white, clad in a long robe; as with other celestial gods, crosses were associated with his representations and shrines. When Cortez landed, the Mexicans were expecting the return of Quetzalcoatl; and, according to Sahagun, the very outlooks who first beheld the ships of the Spaniards had been posted to watch for the coming god. The white men (perhaps the image was aided by their shining armour, their robed priests, their crosses) were inevitably assumed to be the deity, and among the gifts sent to them by Montezuma were the turquoise mask, feather mantle, and other apparel appropriate to the god. It is certain that the belief materially aided the Spaniards in the early stages of their advance, and it is small wonder that the myth which was so helpful to their ambitions should have appealed to their imaginations. The missionary priests, gaining some idea of native traditions and finding among them ideas, emblems, and rites analogous to those of Christendom (the deluge, the cross, baptism, sacraments, confession), not unnaturally saw in the figure of the robed and bearded reformer of religion a Christian teacher, and they were not slow to identify him with St. Thomas, the Apostle. When an almost identical story was found throughout Central America, the Andean region, and, indeed, wide-spread in South America, the same explanation was adopted, and the wanderings of the Saint became vast beyond the dreams of Marco Polo or any other vaunted traveller, while memorials of his miracles are still displayed in regions as remote from Mexico as the basin of La Plata. Naturally, too, the interest of the subject has not waned with time, for whether we view the Quetzal- coatl myth in relation to its association with European ideas or with respect to its aboriginal analogues in the two Americas, it presents a variety of interest scarcely equalled by any other tale of the New World.

The name of the god is formed of quetzal, designating the long, green tail-plumes of Pharomacrus mocinno, and coatl ("serpent"); it means, therefore, "the Green-Feather Snake," and immediately puts Quetzalcoatl into the group of celestial powers of which the plumed serpent is a symbol, among the Hopi and Zuiii to the north as well as among Andean peoples far to the south. Sahagun says that Quetzalcoatl is a wind-god, who "sweeps the roads for the rain-gods, that they may rain." Quetzal-plumes were a symbol of greening vegetation, and it is altogether probable that the Plumed Serpent-God was originally a deity of rain-clouds, the sky-serpent embodiment of the rainbow or the lightning. The turquoise snake-mask or bird-mask, characteristic of the god, is surely an emblem of the skies, and like other sky-gods he carries a serpent-shaped spear-thrower. The beard (which other Mexican deities sometimes wear) is perhaps a symbol of descending rain, perhaps (as on some Navaho figures) of pollen, or fertilization. Curiously enough, Quetzalcoatl is not commonly shown as the white god which the tradition would lead us to expect, but typically with a dark-hued body; it may be that the dark hue and the robe of legend are both emblems of rain-clouds.

The tradition of his whiteness may come from his stellar associations, for though he is sometimes shown with emblems of moon or sun, he is more particularly identified with the morning star. According to the Annals of Quauhtitlan, Quetzalcoatl, when driven from Tollan, immolated himself on the shores of the eastern sea, and from his ashes rose birds with shining feathers (symbols of warrior souls mounting to the sun), while his heart became the Morning Star, wandering for eight days in the underworld before it ascended in splendour. In numerous legends Quetzalcoatl is associated with Tezcatlipoca, commonly as an antagonist; and if we may believe one tale, recounted by Mendieta, Tezcatlipoca, defeating Quetzalcoatl in ball-play (a game directly symbolic of the movements of the heavenly orbs), cast him out of the land into the east, where he encountered the sun and was burned. This story (clearly a variant of the tale of the banishment of Quetzalcoatl told in the Annals of Quauhtitlan and by Sahagun) is interpreted by Seler as a myth of the morning moon, driven back by night (the dark Tezcatlipoca) to be consumed by the rising sun. A reverse story represents Tezcatlipoca, the sun, as stricken down by the club of Quetzalcoatl, transformed into a jaguar, the man-devouring demon of night, while Quetzalcoatl becomes sun in his place. Normally Quetzalcoatl is a god of the eastern heavens, and sometimes he is pictured as the caryatid or upbearer of the sky of that quarter.

Perhaps it is in this character that he was conceived as a lord of life, a meaning naturally intensified by his association with the rejuvenating rains and with the wind, which is the breath of life. A woman who had become pregnant was praised by the relatives of her husband for her faithfulness in religious devotions. "It is for these," they said, "that our lord Quetzalcoatl, author and creator, has vouchsafed this grace even as it was decreed in the sky by that one who is man and woman under the names Ometecutli and Omeciuatl." Moreover the new-born was addressed: "Little son and lord, person of high value, of great price and esteem! precious stone, emerald, topaz, rare plume, fruit of lofty generation! be welcome among us! Thou hast been formed in the highest places, above the ninth heaven, where the two supreme gods dwell. The Divine Majesty hath cast thee in his mould, as one casts a golden bead; thou hast been pierced, like a rich stone artistically wrought, by thy father and mother, the great god and the great goddess, assisted by their son, Quetzalcoatl." The deity also figures as a world creator, as in the Sahagun manuscript in the Academia de la Historia, from which Seler translates:

"And thus said our fathers, our grandfathers,

They said that he made, created, and formed us

Whose creatures we are, Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl;

And he made the heavens, the sun, the earth."

It is in another character, however, that Quetzalcoatl is romantically of most interest. His cult was less sanguinary than that of most Aztec divinities, though assuredly not an- tagonistic to human sacrifice, as some traditions say. He was a penance-inflicting god, perhaps particularly a deity of priests and their lore; yet he was also associated with education and the rearing of the young. He is named as the patron of the arts, the teacher of metallurgy and of letters, and in tradition he is the god of the cultured people of yore from whom the Aztec derived their civilization. A part of the story, as narrated by Sahagun, has been told: how Quetzalcoatl was the aged and wise priest-king of Tollan, driven thence by the magic and guile of Tezcatlipoca and his companions. The tale goes on to tell how Quetzalcoatl, chagrined and ailing, resolved to depart from his kingdom for his ancient home, Tlapallan. He burned his houses built of shell and silver, buried his treasure, changed the cacao-trees into mesquite, and set forth, preceded by servants in the form of birds of rich plumage. Coming to Quauhtitlan, he demanded a mirror and gazing into it, he said, "I am old," wherefore he named the city "the old Quauhtitlan." Seating himself at another place and gazing back upon Tollan, as he wept, his tears pierced the rock, which also bore thenceforth the marks where his hands had rested. He encountered certain magicians, who demanded of him, before they would let him pass, the arts of refining silver, of working in wood, stone, and feathers, and of painting; and as he crossed the sierra, all his companions, who were dwarfs and humpbacks, died of the cold.

PLATE IX

Figures from the Codex Borgia, representing cosmic tutelaries.

The upper figure represents the tree of the Middle Place rising from the body of the Earth Goddess, recumbent upon the spines of the crocodile from which Earth was made. The tree is encircled by the world sea and is surmounted by the Quetzal, whose plumage typifies vegetation; two ears of maize spring up at its roots. The attendant deities are Quetzalcoatl and Macuilxo- chitl, both symbols of fertility. In the figure they are apparently nourishing themselves on the upflowing blood, or vital saps, of the body of Earth. The figure should be compared with the Palenque Cross and Foliate Cross tablets.

The lower figure represents one of the four caryatid-like supporters of the heavens, Huitzilopochtli, as the Atlas of the southern quarter.

Many other localities received memorials of his passage: at one place he played a game of ball, at another shot arrows into a tree so that they formed a cross, at another caused underworld houses to be built all clearly cosmic symbols and finally coming to the sea, he departed for Tlapallan on his serpent-raft. In IxtlilxochitPs history, Quetzalcoatl first appeared in the third period of the world, taught the arts, instituted the worship of the cross "tree of nourishment and of life" and ended the period with his departure. Tradition names the last king of the Toltec "Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl," and it may be assumed as not improbable that stories of the disasters attending the fall of Tollan, under a king bearing the name of the ancient divinity, represent an historical element, confused with nature elements, in the myths of Quetzalcoatl, such an assumption accounting for the heroic glamour surrounding the god, who, like King Arthur, is half kingly mortal, half divinity. In Cholula, whither many of the Toltec were said to have fled with the fall of their empire, was the loftiest pyramid in Mexico, dedicated to Quetzalcoatl and even in the eyes of Aztec conquerors a seat of venerable sanctities the emblem of the culture whose conquest had conquered them.

4. TLALOC AND CHALCHIUHTLICUE

15 The rain-god, Tlaloc, was less important in myth than in cult. He was a deity of great antiquity, and a mountain, east of Tezcuco, bearing his name, was said to have had from remote times a statue of the god, carved in white lava. His especial abode, Tlalocan, supposed to be upon the crests of hills, was rich in all foods and was the home of the maize-goddesses; and there, with his dwarf (or child) servants, Tlaloc possesses four jars from which he pours water down upon the earth. One water is good and causes maize and other fruits to flourish; a second brings cobwebs and blight; a third congeals into frost; a fourth is. followed by dearth of fruit. These are the waters of the four quarters, and only that of the east is good. When the dwarfs smash their jars, there is thunder; and pieces cast below are thunderbolts. The number of the Tlaloque was regarded as great, so that, indeed, every mountain had its Tlaloc.

Like Quetzalcoatl, the god was shown with a serpent-mask, except that Tlaloc's was formed, not of one, but of two serpents; and from the conventionalization of the serpentine coils of this mask came the customary representation of the god's eyes as surrounded by wide, blue circles, and of his lip as formed by a convoluted band from which are fanglike dependencies. The double-headed serpent a symbol no less wide-spread than the plumed serpent is frequently his attribute. His association with mountains brought him also into connexion with volcanoes and fire, and it was he who was said to have presided over the Rain-Sun, one of the cosmogonic epochs, during which there rained, not water, but fire and red-hot stones.

The worship of Tlaloc was among the most ghastly in Mexico. Perhaps for the purpose of keeping up the number of his rain-dwarfs, children were constantly sacrificed to him. If we may believe Sahagun, at the feast of the Tlaloque "they sought out a great number of babes at the breast, which they purchased of their mothers. They chose by preference those who had two crowns in their hair and who had been born under a good sign. They pretended that these would form a more agreeable sacrifice to the gods, to the end that they might obtain rain at the opportune time. . . . They killed a great number of babes each year; and after they had put them to death, they cooked and ate them. ... If the children wept and shed tears abundantly, those who beheld it rejoiced and said that this was a sign of rain very near." No wonder the brave friar turns from his narrative to cry out against such horror. Yet, he says, "the cause of this cruel blindness, of which the poor children were victims, should not be directly imputed to the natural inspirations of their parents, who, indeed, shed abundant tears and delivered themselves to the practice with dolour of soul ; one should rather see therein the hateful and barbarous hand of Satan, our eternal enemy, employing all his malign ruses to urge on to this fatal act." Unfortunately, it is to be suspected that the rite was very farspread, for in the myths of many of the wild Mexican tribes and even in those of the Pueblo tribes north of Mexico the story of the sacrifice of children to the water-gods constantly recurs though, perhaps, this was but the far-cast rumour of the terrible superstition of the south.

The goddess of flowing waters, of springs and rivulets, Chalchiuhtlicue, was regarded as sister of the Tlaloque and was frequently honoured in rites in connexion with them. Like Tlaloc, she played no minor role in the calendric division of powers, and she also ruled over one of the " Suns " of the cosmogonic period. Serpents and maize were associated with her, and like the similar deities she had both her beneficent and malevolent moods, being not merely a cleanser, but also a cause of shipwreck and watery deaths. At the bathing of the new-born she was addressed: "Merciful Lady Chalchiuhtlicue, thy servant here present is come into this world, sent by our father and mother, Ometecutli and Omeciuatl, who reside at the ninth heaven. We know not what gifts he bringeth; we know not what hath been assigned to him from before the beginning of the world, nor with what lot he cometh enveloped. We know not if this lot be good or bad, or to what end he will be followed by ill fortune. We know not what faults or defects he may inherit from his father and mother. Behold him between thy hands! Wash him and deliver him from impurities as thou knowest should be, for he is confided to thy power. Cleanse him of the contaminations he hath received from his parents; let the water take away the soil and the stain, and let him be freed from all taint. May it please thee, goddess, that his heart and his life be purified, that he may dwell in this world in peace and wisdom. May this water take away all ills, for which this babe is put into thy hands, thou who art mother and sister of the gods, and who alone art worthy to possess it and to give it, to wash from him the evils which he beareth from before the beginning of the world. Deign to do this that we ask, now that the child is in thy presence." It is not difficult to see how this rite should have suggested to the first missionaries their own Christian sacrament of baptism.

V. THE POWERS OF LIFE

16 Universally Earth is the mythic Mother of Gods and Men, and Giver of Life; nor does the Mexican pantheon offer an exception to the rule, although its embodiments of the Earth Mother possess associations which give a character of their own. Like similar goddesses, the Mexican Earth Mothers are prophetic and divinatory, and in various forms they appear in the calendric omen-books. They are goddesses of medicine, too, probably owing this function primarily to their association with the sweat-bath, which, in its primitive form of earth-lodge and heated stones, is the fundamental instrument of American Indian therapeutics. It is here, possibly, that these goddesses get their connexion with the fire-gods, of whom they are not infrequently consorts, and with whom they share the butterfly insignia a symbol of fertility, for the fire-god, at earth's centre, was believed to generate the warmth of life. Serpents also are signs of the earth goddesses, not the plumed serpents of the skies, but underworld powers, likewise associated with generation in Aztec symbolism. A third animal connected with generation, and hence with these deities, is the deer the white, dead Deer of the East denoted plenty; the stricken, brown Deer of the North was a symbol of drought, and related to the fire-gods. The eagle, also, is sometimes found associated with the goddesses by a process of indirection, for the eagle is primarily the heavenly warrior, Tonatiuh, the Sun. Frequently, however, the earth goddess is a war-goddess; Coatlicue, mother of the war-god Huitzilopochtli, is an earth deity, wearing the serpent skirt; and it was a wide-spread belief among the Mexicans that the Earth was the first victim offered on the sacrificial stone to the Sun the first, therefore, to die a warrior's death. When a victim was dedicated for sacrifice, therefore, his captor adorned himself in eagle's down in honour, at once, of the Sun and of the goddess who had been the primal offering.

Among the earth goddesses the most famous was Ciuacoatl ("Snake Woman"), whose voice, roaring through the night, betokened war. She was also called Tonantzin ("Our Mother") and, Sahagun says, "these two circumstances give her a resemblance to our mother Eve who was duped by the Serpent." Other names for the same divinity were Ilamatecutli ("the Old Goddess"), sometimes represented as the Earth Toad, Tlatecutli, swallowing a stone knife; Itzpapalotl ("Obsidian Butterfly"), occasionally shown as a deer; Temazcalteci ("Grandmother of the Sweat-Bath"); and Teteoinnan, the Mother of the Gods, who, like several other of the earth goddesses, was also a lunar deity. In her honour a harvest-home was celebrated in which her Huastec priests (for she probably hailed from the eastern coast) bore phallic emblems.

Closely connected with the earth goddesses are their children, the vegetation-deities. Of these the maize-spirits are the most important, maize being the great cereal of the highland region, and, indeed, so much the "corn" of primitive America that the latter word has come to mean maize in the English-speaking parts of the New World. Cinteotl was the maize-god, and Chicomecoatl ("Seven Snakes"), also known as Xilonen, was his female counterpart, their symbol being the young maize-ear. Because of the use of maize as the staff of life, a crown filled with this grain was the symbol of Tonacatecutli ("Lord of our Flesh"), creator-god and food-giver. Pedro de Rios says 17 of him that he was "the first Lord that the world was said to have had, and who, as it pleased him, blew and divided the waters from the heaven and from the earth, which before him were all intermingled; and he it is who disposed them as they now are, and so they called him 'Lord of our Bodies' and 'Lord of the Overflow'; and he gave them all things, and therefore he alone was pictured with the royal crown. He was further called 'Seven Flowers' [Chicomexochitl], because they said that he divided the principalities of the world. He had no temple of any kind, nor were offerings brought to him, because they say he desired them not, as it were to a greater Majesty." This god was also identified with the Milky Way.

PLATE X

Stone mask of Xipe Totec. The face is represented as covered by the skin of a sacrificed victim, flaying being a rite with which this god was honored. The reverse of the mask bears an image of the god in relief. The original is in the British Museum.

Of all Mexican vegetation-deities, however, at once the most important and the most horrible was Xipe Totec ("Our Lord the Flayed"), represented as clad in a human skin, stripped from the body of a sacrificed captive. He was the god of the renewal of vegetation the fresh skin which Earth receives with the recurrent green and his great festival, the Feast of the Man-Flaying, was held in the spring when the fresh verdure was appearing. At this time, men, women, and children captives were sacrificed, their bodies eaten, and the skins flayed from them to be worn by personators of the god. That there was a kind of sacrament in this rite is evident from Sahagun's statement that the captor did not partake of the flesh of his own captive, regarding it as part of his own body. Again, youths clad in skins flayed from sacrificed warriors were called by the god's own name, and they waged mimic warfare with bands pitted against them; if a captive was made, a mock sacrifice was enacted. The famous sacrificio gladiatorio was also celebrated in the god's honour, the victim, with weak weapons, being pitted against strong warriors until he succumbed. The magic properties of the skins torn from victims' bodies is shown by the fact that persons suffering from diseases of the skin and eye wore these trophies for their healing, the period being twenty days. Xipe Totec was clad in a green garment, but yellow was his predominant colour; his ornaments were golden, and he was the patron of gold-workers a symbolism probably related to the ripening grain, for with all that is horrible about him Xipe Totec is at bottom a simple agricultural deity. At his festival were stately areitos, and songs were chanted, one of which is preserved:18

"Thou night-time drinker, why dost thou delay?

Put on thy disguise thy golden garment, put it on!

"My Lord, let thine emerald waters come descending!

Now is the old tree changed to green plumage

The Fire-Snake is transformed into the Quetzal!

" It may be that I am to die, I, the young maize-plant;

Like an emerald is my heart; gold would I see it be;

I shall be happy when first it is ripe the war-chief born!

"My Lord, when there is abundance in the maize-fields,

I shall look to thy mountains, verily thy worshipper;

I shall be happy when first it is ripe the war-chief born!"

Less unattractive is the group of deities of flowers and dancing, games and feasting Xochipilli ("Flower Lord"), Macuilxochitl ("Five Blossoms"), and Ixtlilton ("Little Black-Face"). Xochipilli is in part a divinity of the young maize, probably as pollinating, and is sometimes viewed as a son of Cinteotl. As is natural, he and his brothers are occasionally associated with the pulque-gods, the Centzontotochtin, of whom there were a great number among them Patecatl, lord and discoverer of the ocpatli (the peyote) from which liquor is made, Texcatzoncatl ("Straw Mirror"), Colhuatzincatl ("the Winged"), and Ometochtli ("Two Rabbit") - deities who were supposed to possess their worshippers and to be the real agents of the drunken man's mischief. The more especial associate of the flower-gods, however, is Xochiquetzal ("Flower Feather"), who is said to have been originally the spouse of Tlaloc, but to have been carried away by Tezcatlipoca and to have been established by him as the goddess of love. Her throne is described as being above the ninth heaven, and there is reason to think that in this role she is identical with Tonacaciuatl, the consort of the creator-god, Tonacatecutli. 19 Her home was in Xochitlicacan ("Place of Flowers") in Itzeecayan ("Place of Cool Winds"), or in Tamoanchan, the Paradise of the West the region whence came the Ciuateteo, the ghostly women who at certain seasons swooped down in eagles' form, striking children with epilepsy and inspiring men with lust. Xochiquetzal was, indeed, the patroness of the unmarried women who lived with the young bachelor warriors and marched to war with them, and who sometimes, at the goddess's festival, immolated themselves upon her altars. In a more pleasing aspect she was the deity of weaving and spinning and of making all beautiful and artistic fabrics, and she is portrayed in bright and many-coloured raiment, not forgetting the butterfly at her lips, emblem of life and of the seeker after sweets. In a hymn 20 she is named along with her lover, Piltzintecutli ("Lord of Princes"), who is presumed to be the same as Xochipilli:

"Out of the land of water and mist, I come, Xochiquetzal Out of the land where the Sun enters his house, out of Tamoanchan.

"Weepeth the pious Piltzintecutli;

He seeketh Xochiquetzal.

Dark it is whither I must go."

Seler suggests that this lamentation is perchance the expression of a Proserpina myth of the carrying off into the underworld of the bright goddess of flowers and of the quest for her by her disconsolate lover.