|

|

Atlantis

The Book Of Angels

By D. Bridgman-Metchim

LIBER I

LIBER II | LIBER III

I. THE TEMPLE

II. THE INTERIOR

III. TEKTHAH

IV. THE PALACE

V. THE HALL OF FEASTING

VI. THE GARDEN

VII. THE MARKET-PLACE

VIII. THE MARCH OF HUITZA

IX. AZTA

X. THE THRONE

XI. NOAH

XII. A MAN AND A NATION

XIII. THE CIRCUS

XIV. THE THIRD DAY

XV. THE CHILD OF DOOM

XVI. THE FEAST OF DEATH

XVII. THE PASSING OF TEKTHAH

XVIII. THE HALT OF TRIUMPH

CHAPTER I. THE TEMPLE.

THE days when the sons of Adam increased

and multiplied, and in the days when they overran Atlantis and

builded themselves cities, the noise of their sin rose up the

Heaven. And to me, Asia, an archangel and which stood before the

Throne of God, was given command to go forth upon the Earth and

by reason of my words turn the heart of Man back to the faith of

his fathers, and destroy his groves and altars which he had

raised to the worship of gods created of his evil imaginings,

which were detestable to Us.

THE days when the sons of Adam increased

and multiplied, and in the days when they overran Atlantis and

builded themselves cities, the noise of their sin rose up the

Heaven. And to me, Asia, an archangel and which stood before the

Throne of God, was given command to go forth upon the Earth and

by reason of my words turn the heart of Man back to the faith of

his fathers, and destroy his groves and altars which he had

raised to the worship of gods created of his evil imaginings,

which were detestable to Us.

Now certain also among Us had gone forth and cohabited with the daughters of Man, in mystic visions of the night or by more physical manifestations causing them to conceive and bear children unto them, which was neither seemly nor proper; but in such strong form was the celestial passion manifested in the beings of Earth that even angels stooped to partake of its pleas- ures, (such angels as moved in very close communion with the farther circles, and looked to an extent upon material things). And indeed the separate Female was a mysterious and wonderful creation.

Mrs. Jameson in "Sacred and Legendary Art" gives us

the following: " The great theologians divide the angelic hosts

into three hierarchies, and these again into nine choirs, three

in each hierarchy: according to Dionysius the Areopagite, in the

following order: I. Seraphim, Cherubim, Thrones. 2. Dominations,

Virtues, Powers. 3. Princedoms, Archangels, Angels. The order of

these dominations is not the same in all authorities: according

to the Greek formula, St. Bernard, and the Legenda Aurea, the

Cherubim precede the Seraphim, and in the hymn of St. Ambrose

they have also the precedence To Thee, Cherubim and Seraphim

continually do cry, etc.; but the authority of St. Dionysius

seems to be admitted paramount, for, according to the legend, he

was the convert and intimate friend of St. Paul, and St. Paul,

who had been transported to the seventh heaven, had made him

acquainted with all he had there beheld.

The first three choirs receive their glory immediately from God,

and transmit it on to the second' the second illuminate the

third; the third are placed in relation to the created universe

and man. The first hierarchy are as counsellors, the second as

governors, the third as ministers. The Seraphim are absorbed in

perpetual love and adoration immediately around the throne of

God. The Cherubim know and worship. The Thrones sustain the seat

of the Most High. The Dominations, Virtues and Powers are the

Regents of stars and elements. The three last orders, Princedoms,

Archangels and Angels, are the protectors of the great monarchies

on earth, and the executors of the will of God throughout the

universe.

The term angel is properly applied to all these celestial beings;

but it belongs especially to the last two orders, who are brought

into immediate communication with the human race. The word Angel,

Greek in its origin, signifies a Messenger, or more literally, a

bringer of tidings. In this sense, the Greeks entitle Christ "The

great Angel of the will of God."

For a discussion on the meaning and etymology of Seraphim and

Cherubim see note, cap. XVII., lib. II., where some curious

information is revealed. The word "Archangel" of the text is, in

the original, "Great Angel," or signifies perhaps 'Mighty

Spirit.''

In manifested shape among them were many evil spirits, working confusion by their own confusion, and whereby Man came to know more than was meet that he should: whence would have come much tribulation by reason of his turbulence and ambition, and the use of powers superhuman for the attainment of Earthly things, which is sorcery and witchcraft.

Not very much had I known of the New Creation and of the world among the stars; to me was sufficient the vast delights of space and those far circles where the billows of Life broke upon horizons beyond which flaming worlds fed the Immensity with fire and light; sufficient was the song of endless spheres so justly poised upon the seas of immeasurable air where the rolling wheels of Fate turned, ever moved by the Word, hymned of the winged aons.

And would that I had never left my happy estate, nor ever looked upon thee, Earth world, thou dull spot within the starry coronet that crowns the brows of God. When the noise of thy rebellion and unrest arose, we marvelled; and thinking upon thy smallness it was as the noise of a tiny insect buzzing in a great mansion. Yet, little pest, thy sting is sharp, and many have felt it.

For it was whispered that the beings of Earth were goodly to look upon, and were attractive in their wit and wisdom and high in the sight of our Lord Jehovah, being greatly esteemed that they combined with the subtlety of Heaven a manifested form of Earth. Beautiful in sad truth were they, and excellent in arts, particularly of mischief. And I, who have seen the days when man first came upon Earth, and the last-created man, Adam, and who have looked upon the face of God, bear witness herein to their excellence, and to that ambition that ministered by the female element, medium of Heaven, caused their downfall.

Why should we sing our defeats? Whence the desire that others of Earth shall learn my record of them, that is hidden up in the closing book of the Past? Fain would I lose myself in profound meditation, yet it may not be; and ever arises in sad memory the dreamy glories of Atlantis and starry nights of love. Gone thou art, Zul, city of gods! and thou, my Love, where art thou now? Wilt thou remember when we meet again? O Azta, could I but have led thee in those careless paths where false ambition has no home and the fleeting triumph of dearly-bought glory troubles not! The Siren of Earth, that ever sits beyond your reach and throws gifts of self-esteem whereby ye need no warning and perish in self-created flames, sits not in the lofty groves of Paradise.1

Hear, Peoples of the Future, a recital of days that are past and gone beyond the reach of history a recital ol a power that sought to strive with the creator of itself for a mastery that would have brought but a horror of impotent ruin on Universes unimagined a recital of how the heavenly power of Love brings disaster when not applied in its own spirit and learn, if but in a passing flash of intuition, that misapplied Good begets a more powerful evil than Evil itself can do.

Stooping from Heaven, and full of the trust reposed in me, I sought the Earth lying like a cloudy wonder on the bosom of space; and attaining at length the terrestrial atmosphere with the speed of the Word, and the brightness of the Earth-atoms generating light, stood thereon, an embodied Intellect, upon a vast land, by the side of a lake of water wherein I perceived myself fashioned wondrously. Thereon I gazed in an ecstacy of admiration, not fully understanding as yet that it was my own image, for I had never before taken on any carnal mani- festation; and then confusion overcame me and I rose up and surveyed the surrounding beauties.

And to me was given the power to take on whatsoever form of Earth I wished, which power I perceived to be balanced by a certain dulness of thought and intellect fitted to the heavy atmosphere and the solidity around me.

With what curiosity I gazed on the white swans that skimmed^ the lake, and how I was ravished with the towering beauty of palms and stately trees shadowing the fruitful Earth beneath the blueness of the deeps of sky as apparent. Afar were moun- tain slopes and grotesque yet shapely masses that filled a whole horizon with irregular outlines, and I cried in the language of Earth, How beautiful!

But suddenly the brightness fled. The Earth rose above the sun and there was darkness over everything. In eager haste I mounted into the air and grasped the sword that lay along my thigh, and soon I saw the burning planet and that half the Earth was bright and half was not.

Curious, I lighted down again upon the dark part, near to where I had at first come, and presently the moon shone with a wonderful pure white gleam.

It was night. I stood on the sandy beach of the old sea, that I knew was there long before man came, and that after in more human nature I loved so well because of its restless sorrow; a beach fringed with palm-groves and luxuriant vegetation, with strange animals wandering upon it. I raised my eyes, full of wonder, to the shapely masses rising from its plain, and perceived a city.

The etymology of the Atlantean Zul, which appears to indicate the Sun, is perpetuated in the Akkad Zal, the Aymara Sillo, and the Latin Sol.

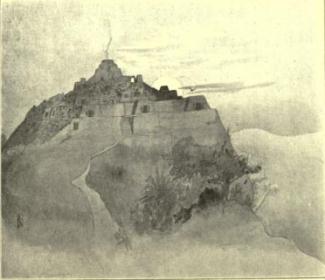

There lay Zul from East to West horizon stretching, dark against the moonlight; and afar, standing out in white sheen and misty beauty, rose tower, pyramid and pylon in endless grouping, mass above mass, terrace above terrace, in cyclopean gloom. Grim, awful and majestic in its immensity of sleeping strength, lay the mighty city; and full of the wonder of the night, I drank my full of the mystery of it and marvelled at the glory of Earth. Methought in the darkness it was the city of Satan and of his legions, and at times I wonder now if I were correct in my thought. Never, ah! never can I forget the stupendous wonder of Zul as it came upon me that night, when as an atom of Earth I stood beneath its majesty.

Up and upward it rose from the bosom of the waters, and within the mighty shadow of its walls I saw gates, massive ports with carven columns and colossal statues, and within the walls, palaces, arches and colonnades, and on this side a wide moat.

I saw the waving flames on temple roofs; I strove to analyse the piles of enormous masonry that rose in confusion the thronging columns, colossi, roofs and towers. This was a city of giants!

There was life within; there was music. Not like the strains my soul loved, but blatant and ribald, and methought, discordant. I perceived many more lights; before a propylon stood a pyramid; and now the light began to return and to disclose monstrous forms and faces, crude clashing colours and rough ornamentations.

The colossi exhibited hideous deformities, and yet there was nought to disgust. Nay; although afterwards I knew them in all their daring obscenity, all was so vast, so enormous, and the grand columns clustered in such confusion of magnificence, that the beastliness of some of their figures was forgotten in the unblushing hugeness that exhibited the deformity so openly. Vast, amorphous shadows formed a background to gray, towering piles of such proportions that caused me to marvel at their grand immensity; square masses of brick and masonry standing there under the shades of the night in bewildering grandeur, simple in their massive immobility, intricate in the dim vistas of colonnade and arch, gate and stairway, column, altar and colossus.

The arch is known in early architecture, but only in a crude form a beam laid on the tops of two pillars, or the structure known as the "false arch," in which bricks or stones project in each layer until they meet at the top.

I saw strange scenes that then I did not understand, and heard sounds of voices, and shrieks; cries that seemed of terror, and the occasional clash of arms. How well, ah, how well was I to know that scene, and hear those sounds in days to come that then I recked not of, being amazed and bewildered by my tumult of emotions and delighted with the strangeness of it all. It was so real, so oppressive and wonderful, and the gray twilight so mysterious, that my senses were intoxicated, and I gazed on the lofty walls and anon over the dark waters with ecstacy.

A sound fell on my ears above all the rest and grew louder and louder. It was the drum of the great temple of Zul, crowning the hill above the waters, that, being struck, rolled out like the awakening voice of Heaven over the city of the Sun, and looking up, I perceived the topmost tower flash like a polished mirror as the first rays of the returning Day struck on it.

I wished to observe what might come, unseen, and, burning with curiosity, lighted on the topmost tower and mingled with the wavy flame, so pure was I then and so powerful. Far above the great ocean that laved the terraced cliff, and far above all the city that spread away into the dark shadows below; beneath me, the temple, story on story, four-sided and flat-topped, each pyramidal and smaller than the one below, reared its mighty mass to Heaven and, from immediately beneath me, the roar of the drum swelled louder and more sonorous, reverberating through the quiet atmosphere; then died slowly away in tremulous waves of sound most beautiful to my ears as they floated afar.

From the very earliest times we find a pyramidal

form used in building, probably not so much for the sake of the

outline as for the fact that this form aids the effort to obtain

vast dimensions with perfect solidity; and the ruins testifying

to this are found in Babylonia, Egypt and America, while the form

is seen in India in her grandest temple, the great pagoda at

Tanjore, rising in 14 stories to a height of nearly 200 ft. from

a base 83 ft. square.

In Babylonia the great mound Babil among the ruins of the

capital, represents the temple of Bel, which was a pyramid of 8

square stages with a winding ascent to the top platform; and the

mound of Birs Nimroud is all that is left of the "temple of the

seven spheres" which was but 156 feet in height, but wonderful by

reason of each of the seven stages being a mass of one colour

different from the others. Of this class we find temples built in

stages of 3, 5, or 7, each of which numbers had a mystic

significance. In Yucatan are found sculptured and architectural

monuments of a coarse character, temples (teocallis) elevated far

above the surrounding buildings on square basements, rising by

huge steps to the summit in the form of a low truncated

pyramid.

The architecture of Egypt is too well known and too familiar to

need any description here, hut by no means is the pyramid an

exclusively Egyptian form, as we see.

Of the architecture of Zul we have no comparative measurements,

and with the one vague statement on p. 14 "greater than great

Babylon," and the bare description, we must imagine an

architecture at least equal to Egypt in her prime. of all the

wonders of these mighty works surely the greatest is the size of

the blocks of stone used in their construction. Professor Lewis

tells us that the very ancient Egyptians must have reached a

proficiency in the mechanical arts of which we can form no

conception, by reason that they were able to quarry rocks of even

granite and to move them to great distances, polishing their

almost iron sides and carving upon them, raising huge masses that

would puzzle our most powerful appliances of to-day to move. Nor

in this again were the Egyptians unique, for in America, at

Txinal. Tiluianaco, Palenque and other places are found

stupendous ruins, of which the huge blocks had been brought into

shape and angle without the use of iron.

And now the flame on the golden tower in which I was, which stood in the centre of the topmost roof wafted by the sea-breezes, seemed to have become absorbed in the glory of the Sun and vanished in the splendour, and from the shadows of the base of the tower a dark figure moved to the edge of the platform facing the brightness. It was a man, and with a great curiosity I gazed upon this one individual atom of the human Life of Karth, that in manifested form could move apart from the rest and live with his own separate functions. And methought there was a strange sympathy between us, for he started and gazed up towards where I hung in airy flame, and then turned and looked long on the flashing beauty of the ocean and the shades beneath. His attitude betokened adoration, and once, twice, three times he bowed his whole body with outstretched hands towards the glory of the sunrise.

Very far off inland I perceived mountains among golden fields of wheat, and other cities, and abundant verdure covered the fair, shadowy Karth, where rivers ran and lakes reflected the tiny pink clouds and the city walls and battlements. After, I learned that the mighty piles were built by the enforced labour of conquered nations of physique and presence immeasurably inferior to the white conquerors in their midst, and who had been there since, as their old traditions told, the entrance of that first man and woman from the East, where great Gabriel guarded the gates of Eden, from whom had sprung a nation that subjugated all around by its arts and prowess.

Lost in contemplation, I surveyed the massive architecture and rejoiced in the solemn and shadowy grandeur of the city as it lay vast and magnificent, with the flames of its many temples leaping and swaying like bright spirits from the Sun that never sleep nor die.

There was a great palace, vast and striking beyond all the rest, enclosing a courtyard of palms and pleasant verdure with red towers and pylons and sweeping terraces of steps, grim and massive as the halls of Hell, and in truth holding as much sin. Yet then I knew it not, and did but gaze in wrapt pleasure on the mighty structures that rose in impious pride above the gloom lying in a wan purple cloud over the gardens that faced the sea beyond the temple, and noted the open spaces of the Circus and the market-place yawning darker than the wide streets. I saw the square pile of the Museum, and palaces of nobles; a round temple, that I afterwards knew to be that of the virgin Goddess Neptsis, whose emblem was a serpent, and whose son, the Lord of Light, was worshipped in Zul, standing conspicuously, near by which were the temples ot Winged things, the Serpent, and the Moon. I saw the fortifications stretching far as the eye could see, and below, the cliff facing the sea, where it declined to the level of the beach and formed a bay; the harbour and water-way and an outer protecting reef of rocks.

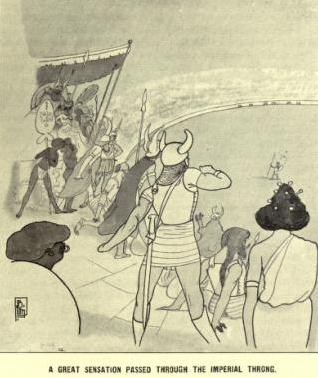

The roar of the drum was answered in the far-echoing spaces for a long time, by others on the surrounding temples, and the music of a myriad birds arose to my delighted ears. I perceived many people to be approaching, and, mounting the stairway running up the eastern front of the temple of " The Lord of Light" Zul came a long procession, the leaders chanting a hymn to the Divinity. Up, up, from the comparative gloom, until the sunlight brightened the yellow mantles of the leading priests and flashed back from helmets and armour and the gorgeous cloaks of those following. It was the procession of the Emperor's household and the great nobles.

Upwards they came with a growing hum of voices and clatter of feet, reaching each terrace successively, where ten men could walk abreast, until a zig-zag of bright colour reached from top to bottom as the priests stepped onto the platform of the highest roof. Following them came many priestesses, for the god Zul was supposed to partake within himself of the nature of both sexes and was equally served by both, and by twos the succes- sors followed them until over fifteen score were gathered beneath my enraptured eyes, delighted to watch their movements and hear all that they said. Beneath their feet plates of gold gleamed sombre in the shadows cast; from their midst arose the golden tower, a pyramid of light, with the imperishable flame waving like a vapour over it, in which I lay entranced. Within this tower was the drum and also within it was kept the victorious standard of the nation, the sacred symbol of victory a Cross with four arms stretching horizontally, signifying the national prowess North, South, East and West the old, rough rally-signal carried by the Emperor Tekthah from the North. Afterwards I knew that all the other cities had, in their Temple of the Sun, that same emblem, feared and venerated throughout the land and Oh, confusion as I write! worshipped as a god. There also stood an altar on that roof, overlaid with gold, and all was bright save the dark man I had first seen come from the tower, which one still remained on the edge looking towards the Sun, and to whom a priestess handed a little smoking bowl.

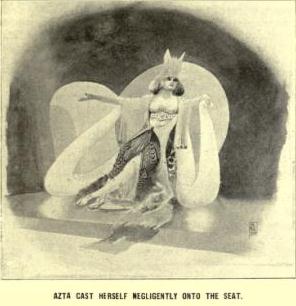

The men before me were tall and godlike and of excellent stature, and I knew them afterwards to be sons of Tekthah and some of the great Tzantans a, and Patriarchs chiefs of the armies, Polemarchs, and tribe leaders. There were women too, on whom I gazed with exceeding admiration, for they were of beautiful form; conspicuous among them stoodest thou, my Love, shining as the moon among stars the Empress Azta, her tawny hair, where golden streams seemed to move in waves of light, fastened above her head by a pin crowned by a butterfly of gold and very large as to size; her yellow eyes heavy and slumbrous and their fires dull, as new awaked from sleep. There were daughters of the Imperial household and of the favoured chiefs, and many that were concubines of Tekthah, which last were very splendid in their* persons and majestic in carriage, and some of them were of other races. Upon their faces lay thickly powdered white pearl-dust, and as they smiled they disclosed their teeth in which were set flashing gems, which gave them a strange appearance.

Some of the men's faces were half concealed by large beards, nearly all black, falling from under their helmets of various shapes according to their rank and following, and flowing over their polished breast-plates. Their hair was as long as that of the women, but coarser, and I learnt that in war the thick tresses were rolled around the neck under closed visors to afford additional protection and make an elastic shield under the metal. Among these ebon chevelures the red-brown one of Huitza, first son of the Tzan Tekthah, (which was King over all the land,) and a very splendid prince, was conspicuous by contrast, with its subtle effects of yellow. From the colour he was supposed to be particularly favoured of the Sun, and the people's hopes leaned to him, their idol, builder of the great province of Tek-Ra: whose Empress-mother, Atlace, had hidden her baby boy, begotten by a celestial lover, until such time as she could mingle him with the unremembered crowd and claim him as a child of the Throne. He stood now the real, though not openly acknowledged, leader of the armies of the mightiest power of Atlantis and the World the Last-created.

My eye roved over the gay throng, but ever returned to Azta; and, O Zul, I looked upon thee, thou fair abode of Evil, greater than Great Babylon, yet unheard of and unknown. Every terrace of the great temple was filled with worshippers, and the roofs of all the other temples were swarming with superstitious idolaters fresh from some wild orgie of the night, and by reason of my perception of spirits I saw their thoughts turning on their wanton excesses and planning more in their hearts, while their crossed hands and bent heads revealed a mockery of adoration. Through a tube the dark man upon the edge of the platform inhaled the smoke from the bowl, which he expelled in clouds towards the four quarters of the heavens,

This custom was always practised as an invocation by the American tribes, among whom tobacco smoking and chewing, (especially the former,) were universal and immemorial usages.

The yellow-robed priests, with wild movements indicative of joy, broke into a weird chant, and in the pauses the faint echo of the distant myriads rose into the pure air with wonderful beauty from below and afar. The god had arisen! a thousand voices shouted in rapture as from the shadows flashed tower and sculptured column, and like a coloured carpet the city rose through the mist.

And who could dream a fairer dream of all the wealth of Earth! There stood revealed the massive grandeur of enormous piles of wonder and awe, scarce o'ertopped by mighty trees of thy many groves, cooled by lakelets and fountains, surrounded by colonnades and courts and the lacy beauty of palms, ablaze with the flaming blossoms of the yellow sartreel bushes and the crimson flowers of the pomegranate, lovely with the columned arches and the statues surpassingly beautiful. O excellent in majesty, would that I had never seen thee!

And then a fleeting idea of my mission ran though me, but I wondered why and how I must fulfil it, my thoughts immediately becoming fixed on the scene before my eyes, causing much perplexity to me, as the dark man which stood against the sun now, with movements representing terror, leaped towards the golden tower, everyone making hasty room. For a short space he disappeared and then, mounting the interior, stood out before me on the highest summit, distinct and clear against the bright sky.

The dark mantle was thrown open torn off cast into the flame, that consumed it in a breath and the pantomime of Night fleeing before Day was over as the High Priest Acoa, the "Voice of God," stood forth in a gleaming garment of the universal yellow and bowed in adoration to the flashing dawn.

Priest of Zul, I rejoice that thy deep lore was locked within thy bosom, for thou knewest indeed more than many of Our- selves. This same was a furious fanatic, believing, heart and soul, in his god, and zealous of the observances of the rites of his temple. Thus ever dwelling on the divinity, with a feverish zeal, he would have sacrificed Tekthah himself or his own person even to the " Lord of Light." How wondrous an influence is fanaticism on the heart of man! Unreasoning, devoted, it is almost noble by its very unselfishness and steadfastness of purpose, by its fury and its zeal.

1. CONCERNING the existence of the semi-mythical island of Atlantis there appears to be no definite information, and it is probable that there never will be; for even could we find its whereabouts stated, the geography of the world has altered since and would render such statement of no avail. In the angelic narrative we get no information as to where it was situated, and as there was no reckoning by latitude and longitude in those days we have to content ourselves with the name, a name that we have often heard of and placed among the myths without thought or reason. We cannot locate this land by any climatic hypothesis, because we find the climate under going apparently a total change in its latter days, possibly even heralding the glacial epoch.

CHAPTER II. THE INTERIOR

THE god comes! A myriad voices hailed him from temple and house-top. The kneeling thousands bowed in real emotional adoration now, the gay crowd on Zul in weary compliance to custom. With the virtue of the dark cloak of Acoa I became more aware of the meaning of all I saw; and bear Thou witness now, O Elohim, ^ who knows and understands all, and perceives how the torment of the spirit forces foolishness from the lips, that to none is showed the hidden things nor the accomplishment of those great affairs that I revealed to such as lived then. For in my impious pride and profound despair I dared to raise the rebellious head, but all those are dead which saw my works and none shall know them more.

I perceived that the people were daringly and defiantly weary, preferring to look with bold glances upon one another to bending their thoughts on worship. But to the mass of the people the glowing orb was a terrific Thing to be appeased the Father of Flame as well as Lord of Light, and King of the leaping Spirits that ever dwelled on their temples ruler of the internal fires that devoured them in thunder, to whom the messenger of Zul flew in the bright lightning and raised in frightful revolt from hidden cares in the mountains; those distant hills, from which, to the west, towering Axatlan lifted her high cone with its coronet of fire and smoke.

There are four names by which God was known of old: Adonai, Lord or Possessor: Shaddai, Almighty: Jehovah, the self-existing one; and Elohim, God, the Covenant-keeper, and Lord of the Universe.

The word Elohim is probably derived from the Hebrew word " Alah " to swear, in support of which we have the Arabic "Allah", God, an almost identical word. Our Lord's last words from the Cross also seem to indicate this meaning: "Eli, Kli, lama sabachthani ". That is to say, "My God, my God''... where is the covenant! And in S. Mark it is still nearer: Eloi, Eloi . . . ". The word Elohim or Elim is the plural of El, chief of the Phoenician divinities.

I understand that the origin of the word "Javeh" or Jehovah appears to be lost in mystery, but apparently indicates One who w, and is Eternal, and true to his covenant: and of these two names, which are frequently used, each with its own significance, Elohim is regarded as treating natural, Jehovah revealed, religion.

From every corner of the great city arose the voice of prayer and praise, and now the High Priest descended from the central tower to the platform. The wild clangour of a song boomed and clashed out, and a silence of death lay over all.

It was the signal for a sacrifice. A death was to take place up there in the pure, holy calm of the early morning, and with that unappeasable appetite of the terrible human heart to gloat over suffering, an appetite that never wearies, the mul- titudes strained their eyes upwards to the temple platform, and those too far off to see were yet pleasantly aware of what was transpiring. For, despite bloody carnivals, brutal scenes of torture and devilish butcheries on a ghastly scale, there was yet something in the solemnity of the hour that startled the ghoulish appetites and made the pulses beat with a pleasant interest.

Up the stairway came the Procession of Atonement, the attendant priests robed in black, the victim in the middle, in silence deep and profound, broken by a weird chant from the priestesses.

The sad procession moved slowly; and moved by an intuition, I knew something dreadful was about to happen, yet, alasl so curious was I, I moved not one step to its hindrance.

I perceived a feeling of natural horror to pervade the multitudes as the dark butcher stood silhouetted against the sky and seized the victim as he stepped on to the platform a grisly pantomime that often resulted in a terrible struggle, the more fearful to those below from its silence and desperate earnestness.

As now, it always resulted in the same thing the victim being carried to the golden altar facing the sunrise and bound down securely. The High Priest raised his voice in a poetic appeal to the Sun, then one gash of a dagger of obsidian laid open the victim's breast, from which the butcher's fingers tore the pulsating heart. Raised aloft, the gory trophy, yet oozing its living blood, was offered to the Sun, and a myriad voices countenanced the murder.

A reproach entered my mind, a feeling of mortified annoyance that I had allowed curiosity to so overcome my just interference. I looked, marvelling, on the victim, for I had no knowledge of death, and perceived him to be a Clay and immoveable; and although I did not quite comprehend what had been done, yet I knew by his former acts and the people's that all was not well, and indeed, most improper. Yet I confess that I did not care to fully comprehend before, being anxious to witness what I might.

In a profound silence the crowds wended their way downwards; the morning worship was over. Through every street they threaded, looking like ants from Zul's stately height, as one vast body made up of tiny units, that, studied individually, exhibited individual characteristics, but were all alike in the issue. The unbiassed mind of one was the unbiassed mind of all. As the pebbles of the beach looked at in a mass form one great plain, yet each has a different shape and no two would fit the same hole; but taken individually or as a mass there is the same groundwork. Also among them may be gems, pearls, diamonds, rubies, sapphires, and the commoner precious stones. I reflected deeply on them and considered their ways and passions without at all understanding what I had already seen, nor dreamed that in those evil hearts burned the seed of the madness that would one day murder the Son of God, their own Creator and mine.

O fools! who worshipped the work and not the Maker, and preferred any god to the all-powerful one! In the empire cities of Chusa, Aten, Lote, Talascan, and a hundred others the same rites had been observed, for though bowing the knee to many divinities, the Lord of Light was esteemed first, the mightiest, most popular and dreaded.

All had gone, and with a desire to allow busy works to cover that weary feeling of reproach, I looked upon the shadowy mass of the temple, whose high front facing the sun was refulgent above the pearly tints below. Considering it well, I entered downwards into the great cool chambers, dark after the morning glow above, and whose thick walls kept out all heat of the Sun, and noted the bold paintings therein. Here all was still and silent; I was alone with those coloured portrayals that spoke to me with an unknown tongue; but after, when I understood, I wondered at the daring audacity that conspired to mingle Heaven and Earth in obscene confusion as there represented. Together with the serpent, which was of that species bearing upon its swelling neck the emblem of the Sun. A great bird appeared to hold high place in these imaginations the vulture, which, preying upon the entrails of the dead, soared to the eternal presence of the gods with the released spirit which would otherwise lose its way. All over the land the foul birds were worshipped as the messengers of the gods. and temples were erected in their honour the honour of a created thing!

The secondary chambers, buried in the enormous mass of the temple, were cold and gloomy, tall columned vaults of shade where no sound ever entered and no air stirred, and where intricate passages led to still darker places beyond number. And here dwelt those priests and priestesses which ministered to the divinity, entombed in the twilight all their lives; for the light, entering by square apertures, or through distant brazen doors which turned within stone pivots, here had to traverse a great thickness of wall, and lighted the inner vaults but feebly, and in awe I gazed around, oppressed by the silence and gloom, while from around peered diabolical faces, grim and immobile, from the colossi supporting the dark roofs. Three on every side they stood, those giant forms of stone, as though they had been there from the beginning of the world, gazing on a dark altar in the central gloom, on which, upheld by three dragons with outstretched wings, was a stone sarcophagus. This chamber was to contain the mortal remains of Tekthah, whose dust, being burned to an ash, would rest in the sarcophagus, built by him for that end, and I wondered at the earthly idea that would wish to lie there in the gloom watched by those stony figures until all of Earth should cease. Ah, man, thou couldst not read the book of fate. On the high roofs were bats that hung like little dark devils and sometimes squeaked as their bones touched one another's, while their evil eyes flared at times upon me.

This may indicate a species of cobra having a circular marking upon it hood, or may refer to the "hood'' itself. Here I've may note thai the only difference between the Indian cobra and the Egyptian is the spectacle-like marking upon the back of the former's neck, both specie having the skin of the neck loose and dilatable at will.

With a strange feeling almost of fear I went downwards into the third floor of chambers, and, as a great moth, flitted here and there in a chamber from which led many galleries. My wings brushed the long webs of spiders in the dark roofs, and upon the gross bosom of a colossus I poised high up to consider the ways stretching in dark avenues hither and thither. In those soundless spaces was no sign of life or movement, but afar off I perceived a light which I believed came from one of the cave-like opening in the outer walls, and speeding thence by an instinct that overcame me, found myself in the chamber of the High Priest.

Buried within those walls, above the earth yet within it, there stood the dark man, bending over a little flame on a brazier, that showed up his clear, hollow, ghastly face and vivid eyes and long white hair, leaving his lower figure in the gloom of the vault, and making the shadows of the place fearful. Methought he gazed anxiously, for he shaded his eyes with both palms and stared with trembling intensity into the flame, that rolled in a purple-red coil topped by the orange brightness, and then turned swiftly towards a faint disc of light away in the gloom. He cried aloud in a fearful voice of rage and command, extending his long, skeleton claws over the flame, his whole form dilated and exalted, his face transformed and his eyes like a devil's.

Wondering that no inspiration entered my mind to address him, I watched, heavy with the great chill and gloom. Suddenly the faint disc brightened until a golden light flooded the vault and struck on the opposite wall, where mystic emblems and figures were grouped in mysterious configuration. It was the light of the Sun which entered and was flashed back from a mirror of obsidian, lighting the whole space and disclosing its contents.

The little flame struggled and coiled. Three of the symbols on the wall moved to a certain place and stood still. Acoa, his face vivified to a terrible degree, watched, and then cried aloud: "Conceive, O thou pregnant one! Bring forth that which is in thee!"

From the flame arose a white amorphous shape, vague and horrible. The man had ceased to breathe and was gazing with an intensity of soul on the spectral figure, that writhed in horrible contortions, yet so indistinct that nought could be seen of what it was. The Thing emitted a very faint sound and then appeared to dissolve in the shadows, and the High Priest fell prone on the floor. The disc was darkening and methought the life of the man was going with the brightness, and I felt sad at the thought what the mortal part was so frail. But, as I stood regarding him, he arose and retired to his stone couch and laid himself thereon, murmuring many things that I did not understand. So I left him.

The fourth chambers were around me, filled with warmth and a deep lurid glow issuing from the centre of the floor where yawned a square bright opening. I was filled with mystery and awe, and the sensation that I was in unknown depths, nor perceived any end to the other chambers stretching right left. The one I stood in was immense, and columns threw great shadows away from the central light that appeared at times to flare more brightly. Pictures with bold, luminous outlines stood out in the farther shadows, mystic representations somewhat similar to those in the first chamber mostly, I found, depicting the wondrous conception of Neptsis and labour with the hermaphrodite Zul. Wild and horrible the phosphoric representations stood, flickering and smoking, and at certain times an indefinable sound echoed round the gloomy vault, while the eyes of the colossi clustering round the columns moved and glittered from on high as though the stony abortions actually lived. No sound disturbed the awful calm where stood those giant forms, save only at times that weird sigh or moan, or what it might have been, that seemed to come from nowhere and return thither.

The Sun is usually a female divinity among Turanians, in earlier religions the moon being often considered of the male sex. The Esquimo regard the moon as a man who visits the earth, and again as a girl whose face is spotted by ashes thrown at her by the sun. Among the Hindu Khasias the Sun is a woman and the moon a man, and in the Andaman Islands the Sun is the wife of the moon. Among aboriginal Hindus the moon is the bride of the Sun.

A fear seized me, a new strange feeling I had never known before, and an inclination to mount thence with speed and seek my native skies; and yet I longed to see and know more, and the curiosity overcame the sudden trembling fear.

And thus in trepidation I explored the fifth central chamber, of which I could see every part, being, as it were, a great pit of light in which tossed a sea of molten gold. Three figures of superior size sat around the bright wonder, with faint, half-imagined shadows playing over them, and my spirit sank with the dread feeling that I stood in some awful presence. Sublime in their majestic stillness they sat, gazing with inscrutable faces downwards, carven from the solid rock that formed the cone of a volcano. In awe I gazed on their calm grandeur, and methought they gazed on me; and I cried in my heart that it was small wonder that man was so esteemed who could create such as this. I yet deemed it might not be of human skill, and believing myself to be beyond the World and in the petrified presence of Those whom God hath chained for ever, I fled upward precipitately, nor ceased my strenuous flight until I hovered far above the city in the gleam of the sun.

CHAPTER III. TEKTHAH.

Now Tekthah was the son of Lamech and brother of Noah the Righteous, remembering also the children of Seth the son of Adam, by his wife Lilith, (which was also his sister) a and the children of all the sons of Adam, spread abroad and multiplied into nations very great and powerful. And being of a bloody nature and of vast ambition he had conceived great ideas, and with all the families of Lamech his father and the families of the sons of Mathusaleh and of all the sons of Enoch and Jared, (the beauty of whose daughters first tempted the sons of God to stray), he had crossed the sea from his own land to found an empire.

Upon the north coast landing, with all their flocks and herds, with cruel arms and many warriors advancing, taught of Azazel in the art of war, the inhabitants were swept before them in ruin and downfall; and along their path of dreadful conquest they built great citadels where the ground was steep and high, half hewn in the rock, half built above, terrace above terrace, with galleries and corridors and ladders to climb upon, which, being pulled up, rendered access impossible. These great Pallos were as one huge fort, full of rooms and very strong, and the chief of them was called Surapa, which was in the province of Astra. Nor was there anything lost by so building, for it was by this discovered where lay the yellow gold and the mines of gems, and where good stone was, and clay for making bricks.

The custom was observed in Egypt of marrying sister to brother in the royal line.

An analogy, which I am not competent to discuss, appears to me to exist between this passage of the Adamites and the legendary start of the Nahoas or Toltecs from the unknown Huelme or Tlapallan, which they left in consequence of a revolution; but which event, however, is said to have taken place shortly before the Christian era The account states apparently that seas and countries intervened between them and their native land before they reached America.

These most remarkable buildings, (i. e. those built of brick or stone,) are apparently in later history only found among the oldest Americans and were generally one huge construction occupying three sides of a court, built on the pyramidal step system, but possessing no apparent internal means of ascent, being mounted by moveable ladders. Such structures were probably the outcome of a vital necessity to protect a small colony of agriculturists from the depredations of less civilized nomads, and their remains are scattered throughout central America and Mexico, on mountain and in forest, many occipied now by Indians. There are the great structures of Pueblo Pintado, the Pueblos of Taos, San Juan, Zuni, Hungo Pavie, and of Pecos, this last estimated by Bandelier to be the largest aboriginal structure of stone in the United States, with a circuit of 1480 ft., 5 storeys in height, and once including by calculation $00 rooms. There is the wonderful rock citadel of Acoma, whose 600 inhabitants live between earih and sky, and Pueblo Bonito, on the Chacos, 1716 ft. in circuit, with 641 rooms and an estimated population of 3000 Indians.

I have seen stated an opinion that the Aztec city of Mexico was but a vast Pueblo, but I think this is highly improbable, as the wonder of such a construction would be certainly greater than an ordinary city of scattered buildings; and it would have taken cleverer men than the followers of Cortez and Piznrro to have fabricated cities and polities like those of Mexico aud Peru.

The northern Indians, the Iroquois and Nez-Perces, also followed the com- munistic idea in their "long-house." such as one described by Lewis and Clarke on the Columbia river; a single house 150 ft. long, built of sticks, straw, and dried grass, containing 24 fires, about double that number of families, and num- bering about 100 fighting men. This represents a communal household of nearly 500 people, and another building of the same race (Nechecolees) was larger, being 226 ft. long. Some tribes of the Amazon and of Borneo have such houses.

It is interesting to trace the etymology of the word Pallo, in Pueblo, palace and the Egyptian Pharaoh, which last word is very curious as embodying the communistic idea, representing the Egyptian words Per-fia, "great house [in which men live]."

And thus with expanding minds they marched southwards until they came to the tall volcano that looked above the waters, whereon they built a Pallo and fought a great battle, establishing themselves there. And for their protection they digged a wide moat, far-reaching and deep; in intervals of peace increasing and multiplying greatly, for that was a very fat land.

And there being but few women, each took unto herself as many husbands as she chose, and round the Pallo, which they called Zul and by which they worshipped the sun, sprang up a village, a town, a city, a great city, a city of grand buildings and later ornamentation, and the temple, built on the crest of the volcano, crowned the height of progress.

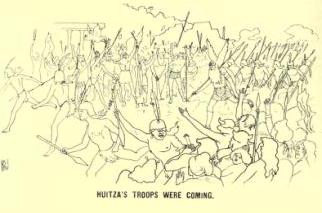

Now in all this time the people were not idly resting on their triumph, for parties continually sallied forth to farther conquests and found new cities. Whereby the Tzantan Iztli swept the far province of Trocoatla, and Rhadaman the son of Maroa, a concubine of Tekthah, carried conquest afar; and many others did likewise, Huitza adding the province of Tek-Ra to the territories of the nation.

Until at last the whole great land of Atlantis was subservient to Tekthah, yet only such parts as were fairest being occupied; and such savage races as menaced the frontiers were kept afar by the terror of their conquerors. These latter also among themselves caused dissensions, for there were ambitious spirits among them who wished to follow the example of Tekthah and form a kingdom for themselves; but as a terrible lesson to all such rebels, the warriors of Rhadaman lay round the pallo of Zoe, (the mother of the dead chief Tygan, who wished to seize a Queendom for herself,) until such time as famine forced them to surrender, and then one hundred and fifty-four of the froward ones were carried to Zul, and died horrible deaths. In likewise fell the pallos of Adiar, Vul and Amarek, and there was given full allegiance to the might of Tekthah.

Then, with peace, there arose a great discussion among the leaders of the allied families as to Tekthah's position, he resting as a ruler over all and dictating affairs. But this with prudent forethought perceiving, he had formed around him a very strong confederacy, there being, besides his own giant brood, his uncle Mehir, (sprung from Azura, daughter of Adam) and the Tzantans Nezca, Amal, Shar-Jatal, Izta, Toloc, Ombar, Colosse and and many more great and powerful.

This name, and that of Avan, are the only names we possess of any daughters of Adam, but an old tradition says he had twenty-three daughters and thirty-three sons.

And especially Nezca advised him strongly as to what policy he should adopt and how he should bind the hearts of people. So the patriarchs and chief warriors in a great council, called upon him to declare his intent, and the issue was that Tekthah's commanding front and gracious promises caused him to be recognized as the ruler over all the land, he pointing out that such course were wise as their brethren might arrive from across the seas and attempt to take from them the fruits of all their heavy labours. But this in the issue they never did, but lay in their forwardness and increasing evil until the waters drowned them with the Earth. Yet Tekthah was also compelled to agree that one chosen of the nation should be always with him to act for the people's welfare and protection.

And being thus, he took on a great pomp and circumstance, yet with politic circumspection; and to please the people (acting also by the advice of Acoa) he caused grand services to be celebrated with horrid bloodshed in the temples of Zul and others, drenching the new altars with the blood of captives. He built a Circus and instituted games and competitions therein, securing powerful adherents by distributing new posts of honour and military glory, and with the enforced labour and aid of thousands of captives working with soaked wedges, rollers, and levers, he constructed his great red palace with stone from the province of Axatlan, and many more buildings of vast size, so that the city of Zul became a wonder and an awe in the land. And in manner becoming to so great a ruler, he established a great national polity, setting up around him certain of his sons and others as judges over the people, to whom was given the power of calling upon the officers of legions to enforce laws, punishments being meted out for various offences. To aid him in government he created princes, counsellors, captains, rulers of territories, governors, treasurers, rulers of tribes and private domestic officers and overseers; while by word of mouth teachers were instructed in many arts and knowledge was greatly propagated.

And Thanaron, the celestial master of Ophie, daughter of Jared, invented a kalendar by which seasons were divided; and Armers showed how to prepare the smoking-herbs for enjoyment of inhalation, many other things being invented and put forward.

All over the land cities began to grow from villages surround- ing pallos to huge walled marvels, taking unto themselves standards and insignia; fields of wheat sprang from the kindly earth, and a navy was built which could sail round the moat of Zul and across the sea to certain islands which lay upon the horizon. The pleasant arts of peace were opened to all to increase, and with security ended that slaughter of female children (which was of necessity when useless mouths but hindered warriors' progress). Yet none might say who was his father, for every woman had many husbands; and indeed wherever I looked the policy of man ran contrary to all natural creation. And by many means the proportion of the females very greatly increased, some being stolen away and sold to a distant master, who disposed of the male offspring as slaves, which soon died, and thus the women were preserved to the great increase of the nation.

And before this had there sprung up a new race a by reason of the Last-created taking unto themselves mistresses from among the captives, and by indiscriminate misdemeanors, which offspring, degraded, and unowned, became servants and slaves, being also encouraged to multiply to aid the supply.

Tekthah, Tzan of Atlantis, with a brilliant court, led the nation afar from its upright paths, followed willingly enough, for indeed human nature ever sins naturally. The cities of the land followed whatsoever the capital led.

The nation halted.

The desire and instinct of progress and development, that, formed by congregation and led by a few energetic minds, precocious children in Life's nursery, manifested itself in the eager restlessness, the collecting into potential communities and the desire for civilization and its benefits, was satisfied with a power that was able to supply itself with every need and luxury, falling before the temptation of slothful enjoyment and turning its vast warlike energies on the satisfaction of carnal lusts. The proud bearing and haughty impetuosity of conscious masters of Earth grew into an arrogance at perceiving the works of their hands flourish and the desire for vast effect gratified; and by reason of the appearance among them of celestial beings who showed them the revelations of mysteries, they gazed entranced with daring knowledge on the hidden things. Forsaking their pure instinctive religion they began to worship idols, and with that strong human feeling that belongs especially to primitive minds, of a desire to worship something visible and tangible, they bowed down to conceptions of their own minds, and the wonders of the Heavens which they represented by them, ot, Such were the Sun, and gems supposed to be born of sunbeams, and the dragon which guarded them and was the emblem of the sun, the moon and stars, the male and female ox, the cat, the frog and other things, to each of which was given a legend which was in part a fact; yet all these were but created things. They believed their forefather Adam to have been a god, and deified all those hoary elders whose terrible years brought such vast experience, magnifying the deeds which they had done until they assumed an appearance surpassing all of Earth. And these they also worshipped under various emblems, nor wag there any end to their imagining.

They became more violent in their ideas, and as with luxury their minds grew licentious and imaginative, so also did their religion, and at length they had the most sensual and debased mythology that the subtlety of their evil minds could conceive; not sparing their ancestors the obscene representations of mystical creation. And in every temple, in every pleasant grove and palmy garden sat enthroned an effigy of some god, degraded and bestial, and each man took unto himself a divinity among manifested animals or insects, eating also food of flesh by subtle reasoning of their minds, and after for their stomach's sake.

The Atlantean religion was in advance, perhaps we may say, of all traces that are understood of the religion of prehistoric times, which is supposed to be Xature-worship alone, with no representations to aid the imagination. But that a people so powerful and of such perceptions should conceive physical forms of natural objects is scarcely surprising.

Friedrich Ratzel mentions the Frog, among many other animals worshipped as gods and adopted as totems by the American Indians, as being met witli in countless typical representations, especially where Toltec civilization reached. Among the Egyptians 1'tah, as creator of man, is a frog.

So falling, those early sinners who came to Atlantis with a pure faith and knowledge of God, raised descendants who fell still farther into idolatry and wickedness, degraded superstition, and still more degraded practices, mingling with them a ferocious and dauntless prowess in war and a luxuriance of living in later days that caused their name to be spoken of with respect and reverence and their power to be undisputed among the races who had been there beyond the legends of all time. Superstitious, ferocious, and of tremendous powers, Atlantis lay under the foot of the sons of Adam; but the world instead of being improved, threatened to sink in a chaos of confusion and blood, and all by the desire of Tekthah, who wished to maintain his high estate.

CHAPTER IV. THE PALACE.

THE palace of Tekthah rose in its colossal grandeur from vast spreading areas of steps, on every landing of which a pair of Andro-sphinxes lay. Built of the red stone of Axatlan, it was as a small city to itself, with its courts and galleries, colonnades, arches and statues and outlying pylon towers, housing within its painted halls many of the great officers of state with their servants, and ladies of high rank which were in the Tizin's train, the astronomers, astrologers and soothsayers, magicians and chemists and many which led Tekthah's inclinations by evil cunning to the great detriment of the land. A structure of grand architecture and gloomy beauty, vast and massive and plain, it never failed to fill me with a. certain awe; indeed a bewildering beauty lay in the spreading fall of the stairways guarded by those stony sentinels on their oblong, flat pedestals, that sat looking with impassive, inscrutable faces on space, and the pairs of colossi which guarded every doorway and were called the Guardians of the entrance; a sense of majesty and power that aspired to great things and could only satisfy the longing by being immense and grand and wondrous. In certain spaces were tall columns of stone of a carnal significance, towering obelisks of which the like were seen all over the land, each one graven with the symbols of genealogy. And each obelisk had a name.

There were gardens surrounding, where feathery palms grew, and yellow sartreels spread their masses of sunny lovliness above the elegant ferns, blended with crimson roses and various flowers of all manners of colours and shapes and perfumes, shaded by great spreading forest trees; and down by the fountains the songs of birds rose from morning to night. Towers supplied these watery jets, the water being pumped up thence by wheels on which generations of slaves had grown up and died.

On a pylon terrace that commanded a view of the ocean the Tzan Tekthah reclined on his couch, attended by one who bore an inhaling-pipe, and a fan-bearer who kept off the rays of the sun and the persecutions of flies. He was a man of great stature, and the white hair that framed his face well became the ruler of so great a nation. White also were his brows and beard, but his face was sensual and cruel, and although he looked a ruler, yet he appeared to have some traits that boded ill for the welfare of his charges. From his mouth and nostrils he blew volumes of fragrant smoke, inhaled from the pipe, in which lay a burning herb, which enjoyment to me appeared at first very curious, but was indulged in by all of the land. The early beauty of the sea and sky arrested his gaze, and I also looked wonderingly to where, within the reef, moved a large black bulk; fine-like arms beat the water and propelled it through the waves, and three gaily-coloured squares of cloth, bellying to the wind, accelerated the speed. I watched it with a lively interest, Tekthah with a listless curiosity; it was one of his vessels, the three-masted warship, Tacoatlanta, bearing at the prow the enormous semblance of a human head, large enough to hold nine hundred warriors, tx, but never venturing more than a mile from shore for fear it would get caught in the current of the great cataract that everyone believed fell over the edge of the world where the Sun rose and where the great sea-animals lived that they saw occasionally monsters of the deep that reared like enormous serpents from the waves.

It is evident that the art of shipbuilding had reached a considerable proficiency in the old days of Atlantis, and in after times we are informed by the best authorities that the Egyptians possessed ships nearly 3000 years B.C. By the cargo consisting of cattle, and the number of rowers employed, these would be of no inconsiderable size, and were not merely large boats or canoes, as, according to the Rev. Edmond Warre, the earliest of all presents us with the peculiar mast of two pieces, stepped apart, but joined at the top. He shows us that " the legend of Helen in Egypt, as well as the numerous references in the Odyssey, point, not only to the attraction that Egypt had for the maritime peoples, but also to long-established habits of navigation and the possession of an art of shipbuilding equal to the construction of sea-going craft capable of carrying a large number of men and a considerable cargo besidts." But in matters maritime the Phoenicians were unsurpassed and the order kept aboard their fine ships, together with their skill of utili/.ing every inch of space, won the later admiration of the Greeks.

It seems strange to learn that some southern Indians had sailing-boats, while the Aztecs, who united witli their predecessors the Toltecs, knew nothing of them, notwithstanding the fact that the latter must have used large crafts to bear them from the legendary Tlapallan to the shores of America.

The vessels of Homer were capable of carrying over too men, but the Atlantean war-ship must have been much larger than any that we read of in ancient times.

The ship entered the harbour, and still Tekthah mused; now scowling up at the temple, where the eunuch priests and their female co-ministers held service to the hermaphrodite Zul, and trying to distinguish some face at that distance, now again scanning the sea. He believed, like most of his people, in what Gorgia the magician said concerning the ebb and flow of the waters: that the gods, the makers of the great animals, who lived over there, drank it down and then threw it up again, and the thunders were the sound of their females in labour producing the monsters.

At the Tzan's feet lay his favorite mistress, Sumar, and on the terrace below, that commanded every approach to the tower, was a company of the Imperial Guards. Their captain was Nezca, a tall prince of exalted beauty, who had as apart- ments the whole base of that tower, for Tekthah feared what he dared not express. For this also it was that he had caused an arm of the sea to flow round the walls of Zul, stopped at each outlet by rocks, that the ebbing tide might not drain it, and had built warships to navigate it if needed.

And thus I perceived the penalty of earthly greatness, and pondered much within my mind if that, Tekthah being over- thrown, the land would be saved from evil. Even should T cause myself to be the Emperor? It was a pleasing thought, but I knew that it might not be; and indeed I had no knowledge of man or his ways, nor the ordering of such.

A trumpet sounded. It was the hour for the morning meal, called the After-worship, and Tekthah arose to enter the Hall of Feasting, for he reclined on a couch which was on the dais at the top of the chamber, and none durst enter until such time as he was seated.

The walls of which splendid apartment were very lofty and of an oblong formation, enclosing a great space with their painted barriers panelled and frescoed in gaudy colourings representing the advent of their race and their wars. Four tall columns supporting the central ceiling, which was painted with scenes as upon the walls. # But how barbarous were their colours when viewed separately, although imposing on the whole I Bright vermilions clashed with ochres and crude greens in all of them: there were sanguinary representations of the chase, in which appeared Mastodons, /3 aurochs, and gigantic stags; and vile pictures of amorous designing, hideous in their beastliness and grotesqueness, and abominable in their atrocious conceptions. Between these panels were long mirrors of gold polished so brightly as to reflect the minutest detail and lending a richer colouring by its own sunny tint.

Attended by his guards the Tzan swept in with his mistress and took his seat. At the sound of a second trumpet the Tizin Azta entered with her guards and attendants, occupying a seat immediately below Tekthah, with her entering Shar-Jatal the Representative of the People; and then, at another trumpet-call, the couches were all filled with the households and suites, numbering three hundred males of various ages, from boys to old men, and ladies greater in number and of the same varia- tions of years. Behind and about them were innumerable attendants, especially around the Tzan, at the back of who stood the Imperial Guards clad in armour, young nobles all, their breastplates of orichalcum fashioned after the emblem of the Sun, cothurns of the same metal, and gold-overlaid shields. For arms they bore long spears with heads of obsidian, and heavy swords of the same; their gleaming helmets were crowned by the plumes of the ostrich, those of the officers being dyed red with minium, and Nezca's being of cunningly wrought gold a mass of beautiful filigree work. And behind each great lord stood his shield-bearer, his cup-bearer, and his pipe-bearer, and many others to be at his instant command; and the ladies also had each her cup-bearer and pipe-bearer among the rest, and to every one there was a fan-bearer to brush away flies.

Sumar lay at the feet of her mighty lord, and on her Rhadaman, the firstborn by a concubine, leader of warriors, whose name was known among all the tribes and among the barbarian hordes afar off, cast a long stare of such a character that, blushing, she averted her face. From her his glance travelled to the Tzan, but as soon as he found he was in danger of being observed he resumed his meal.

The Tzantan Huitza had observed both expressions with a- frown, and I watched keenly, seated among the lower guests, using my perceptions and power to understand all I saw and gathering the meaning then and afterwards. I perceived that he and Rhadaman were both bent upon obtaining sovereign power, and that both as warriors were unequalled in the land, being also greatly beloved by the populace. Yet lately Huitza, ambitious and energetic, blotted out by strenuous works the remembrance of his brother's past deeds, and nought but the sire's power upheld above him the rival.

For Huitza had altered the fashion of war, making his troops most formidable, and causing jealousy to the Tzan, and a great unrest, (he loving not to see one too powerful).

Yet all my regards went forth to the Tizin Azta, and at that first mingling with human beings came my first intuition of my mission, my first trial, my first rebellion.

For of all that godless land Noah was the only just man, being also governor of the province of Tek-Ra, under Huitza, his lord. And it was shown to me that I should uphold Huitza and cause him to become the Tzan, whereby Noah, who was much entrusted by him, would come into great power. Yet being greatly entranced by the beauty of Azta, methought I might win her regards and do also as much good by aiding her to gain the sovereign power, knowing nought of women or why they were not as fitted to rule as men, and repressing the voice that told me that the more earthly mould should greatest excel upon Earth.

In sad mood I gazed around, hesitant, not at all willing to abjure this woman and fulfil my mission unbiassed, but looking upon her until her beauty drowned my reason.

O Azta, dear Love, how queenly wert thou, and how my soul regarded thee! Thou didst not know how I watched thee then, nor conceived the great love which I bore to thee.

To me everything was wondrous and strange and impressive, nor can I tell the peculiar emotions I experienced on perceiving that which was eaten by these godlike forms to be flesh of other animals. It is as a dream those early days of my mission to Earth, the gradual perception of the material grossness of its inhabitants and faint intuition of my end and object.

For ever among the great ones of the land sat the mystics who opened up to their minds the hidden things. So that the counsellors, judges, treasurers, privy officers and all rulers forbore to interest themselves in affairs of Earth, being greatly captivated by strange arguments and visions of delightful things. And especially the queens lent willing ears to such revelations, fascinated by the magic of those evil ones and the things of marvel and awe which they revealed; so that at last none of the people did aught but interest themselves in the most exhilarating things.

The meal was over. The great joints of meat were carried away and the huge, clumsy vesssels, and all manner ot platters of slate, stone or more precious materials carefully lifted and taken to the kitchens by the slaves to be cleaned. Some of the privileged menials remained behind, their position entitling them to the favours extended to the ladies, and they laughed and chattered in broken language to one another, returning sneer for sneer with the haughty queens whenever the latter deigned to notice them. Most of them were slim youths chosen for their beauty, some almost children, covered with a profusion of ornaments; with hair varying from huge frizzled chevelures to oily, coarse masses of curls, all of a black colour; and in like manner their skins varying in shades from yellow to intensest black, and physiognomies of every grade and class.

The Tzan's exodus was the signal for the dispersal, and with noise and laughter the crowd broke up, some to hunt, or play games of ball, others to try their fortune at casting dice, some to transact business of state and some to review the troops. Others went to the vast round building of the Circus that held a semicircle of seats overlooking an arena, where once a year games were held and mock battles took place. These went to practice for the approaching ceremony and view the combatants who were to take part in the display, for the purposes of laying wagers on who should win and who should not, and to see that the brute combatants were well cared for and savage.

I saw Azta cast a glance at the Tzantan Huitza before she* retired to the gardens where she loved to sit and watch the fish in the fountains, and I wondered at its character and that the lord gave no sign of having perceived it. A shade of annoyance clouded the Tizin's face as a cloud coming over the sky a black, furious, sullen look from which her great yellow eyes flared like lightning, while her opening lips disclosed the flaming rubies set in her teeth. She suffered her vivid gaze to fall on Sumar, who yet remained, and who, frightened at their strange beauty, stared with a terrified fascination, as a bird might stare on a serpent; while Azta, enjoying her power, let the long lashes fall softly over them and then averted her head.

I believed her about to kill this one by her glance, for she could never bear that another should stand above herself; and, after, I found that even towards Tekthah, her lord, she nourished an impatient hauteur that the Tzan condescendingly humoured; yet notwithstanding he was her lord such feeling would have been of terrible danger to him if circumstances had favoured the passion for supremacy that caused it. But as concerned Sumar I found there was another motive for her feeling.

She passed out into her garden, attended by the slaves who served her at meals. These, as most of the serfs of the city, were from the dark peoples of the south-east, having black eyes like antelopes and curly hair and great lips. Through the cartilage of the nostrils of each one was thrust a golden skewer, by which they were secured when they were punished for any offence, which many frequently were, being whipped with thongs; and each had, cut on the breast and dyed, the emblem of the particular thing worshipped by his or her owner. Azta's divinity was a butterfly, and the golden emblem overshadowed her proud head, rivers of gold appearing to flow from it as the light moved over the thick silky coils of her hair, that was looped up on either side of her face and confined at the temples by a jewelled strap from which dangled golden plaques, each stamped with the emblem, and representing, I learned, the stars; for Azta's head-dress of state supported the emblem of the moon. A second's hesitation, one swift desperate struggle with my con- science, and I had cast duty aside, preferring to follow this wondrous beauty and feast my eyes upon her lovliness to staying where intuition bade.

Down by the fountains, whose fern-shaded lakes were alive with jewelled fish, was a swinging couch, and to this the Tizin went, and suffered herself to fall upon the soft cushions. She dismissed her retinue, keeping only old Na, a serving- woman, versed in simples and the making of most subtle perfumes the envy of all the queens of Tekthah's court and an endless theme for aspiring gallants.

Of a truth the more I watched this being the more did I love, and half methought to appear suddenly before her in a blaze of glory, being scarce able indeed to resist my love. And surely here was the scene for promoting such a passion; the blue depths above, the flecked shadows from the ferns and magnolias, the tinkle of the waterfall and the sonus of birds among the sartreel bushes; while afar lay entrancing vistas of dazzling surf-lined beaches with their woods and villages, and inland the white towns of Bab- Ala, Lasan, Dar, Ban and Ko.

The Tacoatlanta was moving from the harbour, visible through the trees, and suddenly Azta perceived the black bulk, that looked, with its human head, to be like a great swimming man progressing with a wash of foam at either side, that rolled astern and seethed in a long wake of white, and gazed curiously on it.

Not lone she looked, but turned her face to where rose the pylons and battlements of the palace, seen at intervals, about which flashed the armour of sentinels guarding the monarch who lay within.

"See!" she cried to the old nurse "This day have I lost one of the plates from off my forehead-strap." Yet I knew she only took this as an excuse to vent her temper, and not for sorrow at the loss, which was to be for a great token in after days. "Didst mark the Lady Sumar?" she continued, looking curiously under her lashes at the woman.

"Yea," answered Na; "yet it would ill-become me to speak aught of so exalted an one; but methought she did favour the Lord Mehir overmuch." This she said to soothe Azta, for she knew her regard for Huitza, and feared the wiles of Sumar.

Then, with one of those impetuous motions I learned to love so passionately, Azta turned her lithe body over on the couch,, addressing old Na more than any other object in the landscape but because she could speak. Her countenance unrelieved by aught of colour save on the full lips, framed by waves and masses of living gold, took on, apart from its usual serene calm, a glowing vivacity, and her great eyes, yellow as the liquid amber and lurid as fire, flashed in their vivid beauty, her features expressing joyousness, contempt, savagery, hauteur, and a wild reckless menace.

"Behold me I" she said; "am I not beautiful? who can equal me in all Atlantis? At my feet are all the princes, whom I scorn, even Rhadaman the Superb ha! He, forsooth! There is but one other who is equal to me; who is it, thou old one?"

" There is none. The only one who approaches thee is the Lord Huitza."

Azta's eyes flashed at the name, and to me came an un- comfortable idea.

"It is he, the Lord Huitza! Ay, equal to me, and excelling.

He is a god and all men tremble before him. His face is as the Sun and hast marked his hair, woman? But I have hid from him the love I bear him, preferring to wait until such time when I can make him to rise yet greater in power. Dost hear, old fool?"

"Yea, mistress," answered Na meekly, for Azta's mien was haughty and dangerous as she uttered the words, that were untrue. Then her manner changed and she spoke almost in suppliance "Thinkest thou he is a god to despise all of Earth?" " Belike he is, Lady; who but thyself has so divine a presence?" The Empress passed her hand across her eyes as if she would awake from a vision. "It is enough," she said; "fan me, for I would sleep."

CHAPTER V. THE HALL OF FEASTING.

So great became my love for Azta that I yearned mightily to embrace her, and did but await an opportunity to reveal myself. Forgot I for what I was here, or to study after what fashion I was to act in reforming the sons of Adam; all my thoughts went out to this daughter of Earth and her exceeding lovliness.

Xow Mali was the priest of the temple of the Moon, whom I perceived to be of celestial mould, knowing all the astromomers, astrologers and soothsayers, all such as reckoned analogously concerning man and practised sorcery. Over certain he had a great power, and Azta oft went thither to consult with him, pretending to worship the moon; but I perceived in what manner she worshipped, and how she trusted to his knowledge concerning the means by which she might obtain the sovereign power. Also, as being the Tizin, she had power to enter any temple which she chose, being the High Priestess of the land, and I marvelled that she conferred not with Acoa: but Mali was more of the Earth and practical in its affairs.

Alone with the priest, Azta spoke to him on matters other than of worship, calling him her old counsellor and bidding him speak if he had aught to say. "Zul awaits thee," she said, with a swift glance at him. He smiled, and I knew that evil reigned in his heart, yet of what fashion I knew not, but it was an unpleasant look that he wore, and methought Azta seemed displeased as she gazed haughtily at the mystic insignia and the dark corridors.

"My daughter," he said, "haste will ruin all, and care must be taken in selecting our tools, or they will wound the hand that guides them. The Lord Shar-Jatal, whom Tekthah favours, is in the toils of the Lady Pocatepa, who will bid him administer a potion prepared by me to Tekthah. But thou must first take Rhadaman to be thy right hand wherewith to gain the throne; with him thou canst make terms, he being thy suppliant slave; and thou, being more powerful than he, canst so secure thyself that thou wilt reign alone and supreme. Thou understandest? "

"But of Huitza?"