Chapter XIII

Nisus And Scylla, Echo And Narcissus, Clytie, Hero And Leander

NISUS AND SCYLLA.

From Ovid's Metamorphoses Book VIII: 90-100 Scylla with Lock of Nisus' hair

MINOS, king of Crete, made war upon Megara. Nisus was king of Megara, and Scylla was his daughter. The siege had now lasted six months and the city still held out, for it was decreed by fate that it should not be taken so long as a certain purple lock, which glittered among the hair of King Nisus, remained on his head.

See: Megara in Herodotus The History. The Ninth Book: Calliope

There was a tower on the city walls, which overlooked the plain where Minos and his army were encamped.

To this tower Scylla used to repair, and look abroad over the tents of the hostile army. The siege had lasted so long that she had learned to distinguish the persons of the leaders. Minos, in particular, excited her admiration. Arrayed in his helmet, and bearing his shield, she admired his graceful deportment; if he threw his javelin skill seemed combined with force in the discharge; if he drew his bow Apollo himself could not have done it more gracefully.

But when he laid aside his helmet, and in his purple robes bestrode his white horse with its gay caparisons, and reined in its foaming mouth, the daughter of Nisus was hardly mistress of herself; she was almost frantic with admiration. She envied the weapon that he grasped, the reins that he held.

She felt as if she could, if it were possible, go to him through the hostile ranks; she felt an impulse to cast herself down from the tower into the midst of his camp, or to open the gates to him, or to do anything else, so only it might gratify Minos. As she sat in the tower, she talked thus with herself:

“I know not whether to rejoice or grieve at this sad war. I grieve that Minos is our enemy; but I rejoice at any cause that brings him to my sight. Perhaps he would be willing to grant us peace, and receive me as a hostage. I would fly down, if I could, and alight in his camp, and tell him that we yield ourselves to his mercy. But then, to betray my father! No! rather would I never see Minos again.

And yet no doubt it is sometimes the best thing for a city to be conquered, when the conqueror is clement and generous. Minos certainly has right on his side. I think we shall be conquered; and if that must be the end of it, why should not love unbar the gates to him, instead of leaving it to be done by war? Better spare delay and slaughter if we can. And O if any one should wound or kill Minos! No one surely would have the heart to do it; yet ignorantly, not knowing him, one might. I will, I will surrender myself to him, with my country as a dowry, and so put an end to the war.

But how? The gates are guarded, and my father keeps the keys; he only stands in my way. O that it might please the gods to take him away! But why ask the gods to do it? Another woman, loving as I do, would remove with her own hands whatever stood in the way of her love. And can any other woman dare more than I? I would encounter fire and sword to gain my object; but here there is no need of fire and sword. I only need my father’s purple lock. More precious than gold to me, that will give me all I wish.”

While she thus reasoned night came on, and soon the whole palace was buried in sleep. She entered her father’s bedchamber and cut off the fatal lock; then passed out of the city and entered the enemy’s camp. She demanded to be led to the king, and thus addressed him:

“I am Scylla, the daughter of Nisus. I surrender to you my country and my father’s house. I ask no reward but yourself: for love of you I have done it. See here the purple lock! With this I give you my father and his kingdom.”

She held out her hand with the fatal spoil. Minos shrunk back and refused to touch it.

“The gods destroy thee, infamous woman,” he exclaimed; “disgrace of our time! May neither earth nor sea yield thee a resting–place! Surely, my Crete, where Jove himself was cradled, shall not be polluted with such a monster!”

Thus he said, and gave orders that equitable terms should be allowed to the conquered city, and that the fleet should immediately sail from the island.

Scylla was frantic.

“Ungrateful man,” she exclaimed, “is it thus you leave me?– me who have given you victory,– who have sacrificed for you parent and country! I am guilty, I confess, and deserve to die, but not by your hand.”

As the ships left the shore, she leaped into the water, and seizing the rudder of the one which carried Minos, she was borne along an unwelcome companion of their course. A sea–eagle soaring aloft,– it was her father who had been changed into that form,– seeing her, pounced down upon her, and struck her with his beak and claws.

In terror she let go the ship and would have fallen into the water, but some pitying deity changed her into a bird. The sea–eagle still cherishes the old animosity; and whenever he espies her in his lofty flight you may see him dart down upon her, with beak and claws, to take vengeance for the ancient crime.

[See: The Story of Nisus and Scylla]

[See: Apollodorus The Epitome]

[See: The Sirens; Scylla and Charybdis; Thrinacia From Stories from the Odyssey, by H. L. Havell ]

ECHO AND NARCISSUS.

Echo was a beautiful nymph, fond of the woods and hills, where she devoted herself to woodland sports. She was a favourite of Diana, and attended her in the chase. But Echo had one failing; she was fond of talking, and whether in chat or argument, would have the last word.

One day Juno was seeking her husband, who, she had reason to fear, was amusing himself among the nymphs. Echo by her talk contrived to detain the goddess till the nymphs made their escape. When Juno discovered it, she passed sentence upon Echo in these words:

“You shall forfeit the use of that tongue with which you have cheated me, except for that one purpose you are so fond of– reply. You shall still have the last word, but no power to speak first.”

This nymph saw Narcissus, a beautiful youth, as he pursued the chase upon the mountains. She loved him and followed his footsteps. O how she longed to address him in the softest accents, and win him to converse! but it was not in her power. She waited with impatience for him to speak first, and had her answer ready. One day the youth, being separated from his companions, shouted aloud,

“Who’s here?”

Echo replied,

Echo and Narcissus by John William Waterhouse, 1903

“Here.”

Narcissus looked around, but seeing no one, called out,

“Come.”

Echo answered,

“Come.”

As no one came, Narcissus called again,

“Why do you shun me?”

Echo asked the same question.

“Let us join one another,”

said the youth. The maid answered with all her heart in the same words, and hastened to the spot, ready to throw her arms about his neck. He started back, exclaiming,

“Hands off! I would rather die than you should have me!”

“Have me,” said she; but it was all in vain. He left her, and she went to hide her blushes in the recesses of the woods.

From that time forth she lived in caves and among mountain cliffs. Her form faded with grief, till at last all her flesh shrank away. Her bones were changed into rocks and there was nothing left of her but her voice. With that she is still ready to reply to any one who calls her, and keeps up her old habit of having the last word.

Narcissus’s cruelty in this case was not the only instance. He shunned all the rest of the nymphs, as he had done poor Echo. One day a maiden who had in vain endeavoured to attract him uttered a prayer that he might some time or other feel what it was to love and meet no return of affection. The avenging goddess heard and granted the prayer.

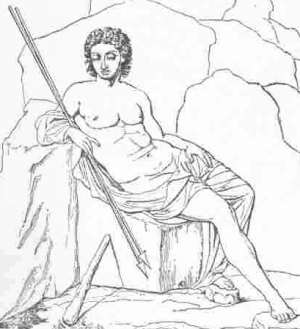

Narcissus. From the 1908 Edition p. 121

There was a clear fountain, with water like silver, to which the shepherds never drove their flocks, nor the mountain goats resorted, nor any of the beasts of the forests; neither was it defaced with fallen leaves or branches; but the grass grew fresh around it, and the rocks sheltered it from the sun.

Hither came one day the youth, fatigued with hunting, heated and thirsty. He stooped down to drink, and saw his own image in the water; he thought it was some beautiful water–spirit living in the fountain. He stood gazing with admiration at those bright eyes, those locks curled like the locks of Bacchus or Apollo, the rounded cheeks, the ivory neck, the parted lips, and the glow of health and exercise over all. He fell in love with himself. He brought his lips near to take a kiss; he plunged his arms in to embrace the beloved object. It fled at the touch, but returned again after a moment and renewed the fascination.

He could not tear himself away; he lost all thought of food or rest. while he hovered over the brink of the fountain gazing upon his own image. He talked with the supposed spirit:

“Why, beautiful being, do you shun me? Surely my face is not one to repel you. The nymphs love me, and you yourself look not indifferent upon me. When I stretch forth my arms you do the same; and you smile upon me and answer my beckonings with the like.”

His tears fell into the water and disturbed the image. As he saw it depart, he exclaimed,

“Stay, I entreat you! Let me at least gaze upon you, if I may not touch you.”

With this, and much more of the same kind, he cherished the flame that consumed him, so that by degrees be lost his colour, his vigour, and the beauty which formerly had so charmed the nymph Echo. She kept near him, however, and when he exclaimed,

“Alas! alas!

she answered him with the same words. He pined away and died; and when his shade passed the Stygian river, it leaned over the boat to catch a look of itself in the waters.

The nymphs mourned for him, especially the water–nymphs; and when they smote their breasts Echo smote hers also. They prepared a funeral pile and would have burned the body, but it was nowhere to be found; but in its place a flower, purple within, and surrounded with white leaves, which bears the name and preserves the memory of Narcissus.

Milton alludes to the story of Echo and Narcissus in the Lady’s song in “Comus.” She is seeking her brothers in the forest, and sings to attract their attention:

“Sweet Echo, sweetest nymph, that liv’st unseen

Within thy aery shell

By slow Meander’s margent green,

And in the violet-embroidered vale,

Where the love-lorn nightingale

Nightly to thee her sad song mourneth well;

Canst thou not tell me of a gentle pair

That likest thy Narcissus are?

O, if thou have

Hid them in some flowery cave,

Tell me but where,

Sweet queen of parly, daughter of the sphere,

So may’st thou be translated to the skies,

And give resounding grace to all heaven’s harmonies.”

[See: Comus By Milton]

Milton has imitated the story of Narcissus in the account which he makes Eve give of the first sight of herself reflected in the fountain.

“That day I oft remember when from sleep

I first awaked, and found myself reposed

Under a shade on flowers, much wondering where

And what I was, whence thither brought, and how

Not distant far from thence a murmuring sound

Of waters issued from a cave, and spread

Into a liquid plain, then stood unmoved

Pure as the expanse of heaven; I tither went

With unexperienced thought, and laid me down

On the green bank, to look into the clear

Smooth lake that to me seemed another sky.

As I bent down to look, just opposite

A shape within the watery gleam appeared,

Bending to look on me. I started back;

It started back; but pleased I soon returned,

Pleased it returned as soon with answering looks

Of sympathy and love. There had I fixed

Mine eyes till now, and pined with vain desire,

Had not a voice thus warned me: ‘What thou seest,

What there thou seest, fair creature, is thyself;” etc.

Paradise Lost, Book IV.

No one of the fables of antiquity has been oftener alluded to by the poets than that of Narcissus. Here are two epigrams which treat it in different ways. The first is by Goldsmith:

“ON A BEAUTIFUL YOUTH, STRUCK BLIND BY LIGHTNING.

“Sure ‘twas by Providence designed

Rather in pity than in hate,

That he should be like Cupid blind,

To save him from Narcissus’ fate.”

The other is by Cowper:

“ON AN UGLY FELLOW.

“Beware, my friend, of crystal brook

Or fountain, lest that hideous hook,

Thy nose, thou chance to see;

Narcissus’ fate would then be thine,

And self-detested thou would’st pine,

As self-enamoured he.”

CLYTIE.

Clytie was a water–nymph and in love with Apollo, who made her no return. So she pined away, sitting all day long upon the cold ground, with her unbound tresses streaming over her shoulders. Nine days she sat and tasted neither food nor drink, her own tears, and the chilly dew her only food. She gazed on the sun when he rose, and as he passed through his daily course to his setting; she saw no other object, her face turned constantly on him. At last, they say, her limbs rooted in the ground, her face became the sunflower which turns on its stem so as always to face the sun throughout its daily course; for it retains to that extent the feeling of the nymph from whom it sprang.

Hood, in his “Flowers,” thus alludes to Clytie:

A 1680s marble statue of Clytie by Filippo Parodi, from the Galleria di Palazzo Reale, Genoa

“I will not have the mad Clytie:

Whose head is turned by the sun;

The tulip is a courtly quean,

Whom therefore I will shun;

The cowslip is a country wench,

The violet is a nun;-

But I will woo the dainty rose,

The queen of every one.”

The pea is but a wanton witch,

In too much haste to wed,

And clasps her rings on every hand;

The wolfsbane I should dread;

Nor will I dreary rosemarye,

That always mourns the dead;

But I will woo the dainty rose,

With her cheeks of tender red.

The lily is all in white, like a saint,

And so is no mate for me,

And the daisy's cheek is tipp’d with a blush,

She is of such low degree;

Jasmine is sweet, and has many loves,

And the broom's betroth'd to the bee;

But I will plight with the dainty rose,

For fairest of all is she.

The sunflower is a favourite emblem of constancy. Thus Moore

uses it in his:

Believe Me If All Those Endearing Young Charms.

Believe me, if all those endearing young charms,

Which I gaze on so fondly today,

Were to change by to-morrow, and fleet in my arms,

Like fairy-gifts fading away,

Thou wouldst still be adored, as this moment thou art.

Let thy loveliness fade as it will.

And around the dear ruin each wish of my heart

Would entwine itself verdantly still.

It is not while beauty and youth are thine own,

And thy cheeks unprofaned by a tear,

That the fervor and faith of a soul can be known,

To which time will but make thee more dear;

No, the heart that has truly loved never forgets,

But as truly loves on to the close,

As the sun-flower turns on her god, when he sets,

The same look which she turned when he rose.

From The Complete Poems of Sir Thomas Moore

[See: The Folk-Lore Of Plants by T.F. Thiselton-Dyer]

[See: The Transformation of Clytie from Metamorphoses by Ovid]

HERO AND LEANDER.

Leander was a youth of Abydos, a town of the Asian side of the strait which separates Asia and Europe. On the opposite shore, in the town of Sestos, lived the maiden Hero, a priestess of Venus. Leander loved her, and used to swim the strait nightly to enjoy the company of his mistress, guided by a torch which she reared upon the tower for the purpose. But one night a tempest arose and the sea was rough; his strength failed, and he was drowned. The waves bore his body to the European shore, where Hero became aware of his death, and in her despair cast herself down from the tower into the sea and perished.

The following sonnet is by Keats:

“ON A PICTURE OF LEANDER.

“Come hither all sweet Maidens soberly

Down looking aye, and with a chasten’d light

Hid in the fringes of your eyelids white,

And meekly let your fair hands joined be,

As if so gentle that ye could not see,

Untouch’d, a victim of your beauty bright,

Sinking away to his young spirit’s night,

Sinking bewilder’d ‘mid the dreary sea.

‘Tis young Leander toiling to his death.

Nigh swooning he doth purse his weary lips

For Hero’s cheek, and smiles against her smile.

O horrid dream! see how his body dips

Dead-heavy; arms and shoulders gleam awhile;

He’s gone; up bubbles all his amorous breath!”

[See: Poems 1817 By John Keats]

The story of Leander’s swimming the Hellespont was looked upon as fabulous, and the feat considered impossible, till Lord Byron proved its possibility by performing it himself. In the “Bride of Abydos” he says,

“These limbs that buoyant wave hath borne.”

The distance in the narrowest part is almost a mile, and there is a constant current setting out from the Sea of Marmora into the Archipelago. Since Byron’s time the feat has been achieved by others; but it yet remains a test of strength and skill in the art of swimming sufficient. to give a wide and lasting celebrity to any one of our readers who may dare to make the attempt and succeed in accomplishing it.

In the beginning, of the second canto of the same poem, Byron thus alludes to this story:

“The winds are high on Helle’s wave,

As on that night of stormiest water,

When Love, who sent, forgot to save

The young, the beautiful, the brave,

The lonely hope of Sestos’ daughter.

O, when alone along the sky

The turret-torch was blazing high,

Though rising gale and breaking foam,

And shrieking sea-birds warned him home;

And clouds aloft and tides below,

With signs and sounds forbade to go,

He could not see, he would not hear

Or sound or sight foreboding fear.

His eye but saw that light of love,

The only star it hailed above;

His ear but rang with Hero’s song,

‘Ye waves, divide not lovers long.’

That tale is old, but love anew

May nerve young hearts to prove as true.”

[See: The Bride of Abydos]

[See: Hero and Leander by Christopher Marlowe

[See: Written After Swimming from Sestos to Abydos by Lord Byron